Climbing into the 1% in the Age of Capitalist Excess

You can steal millions of dollars if you work for the right people, apparently.

Back in the day, when I used to teach in the MBA program of my university, a favourite topic about which I could fulminate at length was the problem of wealth inequality. Depending on your viewpoint, this can be considered either a question of managing the asymmetric distribution of capital assets or fighting the tyranny of blood-sucking leech-capitalism. Either way, the point is that in all major developed societies, there is a gross distortion in the way capital wealth is distributed across the population, although some developed societies are worse than others. The US, predictably, is worst of all.

Now when I used to bang on about this, some of my students (mostly, ahem, Venezuelans – you know who you are), would immediately hear disturbing echoes of Chavismo in my remarks, a Pavlovian response to any discourse that touches on societal wealth imbalance. But I don’t want to just single them out, because plenty of others, when confronted with the facts of wealth inequality, would immediately assume it was a prelude to advocating for some kind of radical socialist redistribution scheme.

Now it is a fact, as amply demonstrated by scholars like Edward Wolff or Thomas Piketty (cf. his important but so-long-nobody-read-it book Capital in the Twenty-First Century), that any economy which derives investment via the transfer of private capital across markets will produce an imbalance of wealth accumulation as a result. This is for the simple fact, as Picketty shows, that capital wealth increases on average at a significantly higher rate than income-accumulated wealth. This means that capital-driven investment, when privatized, will produce a capital-owning class. So if you want to have the benefits of a capital market system – producing amazing things like iPhones, Grok, or (if you’re of a certain age like me) Shamwow! – the inevitable trade-off is going to be a resulting societal imbalance in wealth. It’s just the math.

And it really is the math. The long-term distribution of societal wealth is described by a Pareto distribution. (Here’s the unreadable Wikipedia article, which is helpful to exactly nobody since if you can wade through that you already know what a Pareto distribution is). In layman’s terms, it’s the famous 80-20 rule (e.g. 80% of Big Macs are consumed by 20% of Micky-D customers, etc.). Vilfredo Pareto, the 19th century Italian sociologist who came up with the rule, actually discovered it by studying … guess what? Wealth distribution in Italy. So while the Pareto distribution shows up all over the place (not always though: 80% of the sleeping in my class comes from 80% of the students), its original derivation was as a principle for how wealth settles across a social system.

Now the Pareto distribution of wealth can be observed across time and place. What modern capitalism has done is intensified the Pareto effect. This is common to all free-market economies, but the US (of course) makes the case most dramatically. According to the US government’s own statistics (at least until the current administration decides to change them by firing the statisticians), the top 10% controls about 70% of all wealth. And, as has been pointed out by lots of folks, these numbers are themselves not accurate since the wealthy have ways of hiding their wealth, so the real picture is presumably rather more lopsided.

This is already a distortion of a normal Pareto, but it’s more distorted than even this figure would suggest. That’s because about half of that top-ten wealth is concentrated in the hands of just the top 1% (roughly 31% of all national wealth). But it gets worse than that. Because roughly half of that top 1% wealth is concentrated in the hands of the top 0.1% (14%). There’s a pattern here: half of the share is concentrated in the top 10% of the category (wonderfully logarithmic pattern that), which is itself, if you think about it, a distortion of the Pareto effect. Math. Who knew?

So this means the wealthy are overwhelmed by the super wealthy. But those folks are overwhelmed in turn by the ultra-wealthy. And even they are just a smudge on the balance sheet of the super-ultra-wealthy. I am running out of adjectives here, but at some point you get to that handful of Musks and Gates and Bezos’ who are each worth the GDP of small countries.

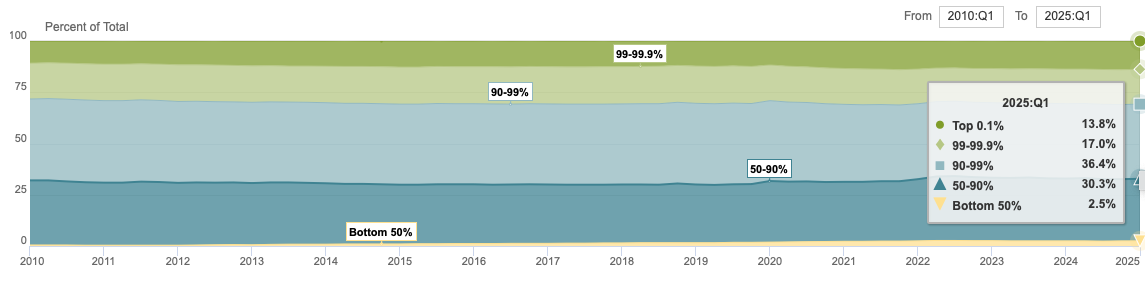

Here’s a graph that shows what this looks like:

That almost invisible thin yellow line relegated to the bottom of this graph – I mean can you even see it? If you are reading this on your phone, flip it to landscape view and then zoom in. Yea, that line. That’s half - HALF - the country. Basically invisible in terms of national wealth.

Obvs there’s a big problem when half the country is essentially invisible while the top 0,1% or 0,01% stand athwart the system, highly visible and ultra-wealthy. Over time, this is likely to lead to what the Ancient Greeks called stasis – a kind of revolution, but more relevant really to human affairs since it emphasizes the chaotic dissolution of social stability rather than a structured political agenda promising radical change. But before you get to that point, as you're living through the reality of this extreme concentration of wealth – what does that actually look like?

Okay, all that was supposed to be an introduction but somehow turned into my typical screed when thinking about this topic, so apologies (the unsubscribe button is somewhere hereabouts). I got to thinking about all this again, when I stumbled across this interesting story while scrolling on Bluesky: “How a Fake Philanthropist Fooled the Frick.” The TLDR is: slick grifter steals from wealthy patrons and buys himself respectability by donating large sums of this stolen money to established institutions like the Frick Museum and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. (If you’re interested, a more detailed account was published in New York Magazine.)

Part of this is an old story. The point about gaining cred and social oomph by dumping buckets of cash to worthy but broke cultural institutions has a long pedigree. This practice is, I think, of Anglo-American origin: industrialists who gained great wealth in the nineteenth century nonetheless found that high society was firmly closed to them because they were, deep down, rough-hewn plebs. But you can’t keep a good entrepreneur down, so these crafty folks devised all kinds of ways to acquire the respectability they lacked by using the thing they had most of, which – if you’re following closely here – you’ll realise is MONEY.

Marrying into noble but impoverished lineages was one method. You have almost certainly never heard of Leonard Jerome (and if you have, give yourself TWO gold stars as that’s genuinely impressive), but he was a highly successful what the Brits used to term “stock-jobber” but we now call “financier” (ah, language). Faced with fat piles of dosh on one side and questionable social standing on the other (although he, too, had married money - it helps), he stuffed (figuratively) large wads of cash into the corsets of his daughters and sent them off to Britain to find a man. And one of them did – and produced no less than Winston Churchill as a result. Well done Leonard!

But that doesn’t benefit you directly, just your (often ungrateful) offspring, so a better way is to start pumping cash into institutions that scream class and status (and caring and all the I’m-a-decent-person signalling that well-crafted philanthropy can bring), but are also chronically in need of cash. And in the cultural world created by late-stage capitalism, that need doesn’t even have to be that chronic. Prestigious universities now routinely auction off their prestige to raise cash. Back in the 1940s, Princeton renamed its school for diplomats the “Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs,” because, you know, Woodrow Wilson cared about international affairs, and was a Princeton graduate. Oh, and he was PRESIDENT of the United States. Who, by contrast, is John A. Paulson or Kenneth C. Griffin? I dunno, but if you want the answer, ask a Harvard grad, since they both have schools there named after them. Paulson (I’ve just checked) made his money by shorting the housing market back in 2008. So, that’s nice. Lots of middling folks who lost their house when they went sideways on their mortgage payments can be comforted by the fact that some of the wealth generated by the “asymmetric” market went to making the lives of Harvard students a little more comfortable.

(As an aside, why is the middle initial always included in these things? It seems like a general rule of thumb that if you spot a middle initial on a named institution, it’s a dead giveaway that it is an exercise in status-building. My guess is it’s the “John - F. - Kennedy” effect. Just sounds classier, like, oh are you Bill Nobody? No bitch, I am William F. Nobody, now go make me a sandwich. I dunno, just a theory.)

Back to the story. Our grifter, named Matthew Christopher Pietras (pictured above), was apparently a keen student of this acquire-cultural-capital-through-philanthropy school, and realized that if he started funnelling donations to places that were big on status but short on cash, he, too, could rise from random nobody to society bigwig. And to get there all he had to do was steal tens of millions of dollars from his employers. He siphoned off this money and then redirected it, in addition to funding his own lavish lifestyle, to places like the New York Public Library, the Frick, and the Met – and even managed to get himself onto the board of these highfalutin institutions.

Matthew knew that lavishness needs legitimacy. Sure, you can be Matthew Pietras and book a private plane for you and your friends for a weekend in the Caribbean and post it all over the Insta (he did this). Fun, but that’s not going to get you respectability. However, if NYC Libraries Dean’s Advisory Council Chairman, and Member of the Board of Directors of the Metropolitan Opera, and benefactor behind the Matthew C. (take note) Pietras Head of Music and Performance at the Frick Museum, if that Matthew Pietras books a private plane for his friends for a weekend in the Caribbean, well that’s the whole package right there. More champagne anyone?

My point is that Pietras managed to insinuate himself into the top echelons of New York Society (New York, people – not some podunk burg like Dallas here) via donations to leading cultural institutions using money that he had stolen – and nobody noticed. For a decade!

Who, one naturally wants to know, were the true, if unknowing, benefactors of this generosity? They were his employers. One was the “conceptual artist” Gregory Soros, son of George Soros, stock-jobber financier. (And btw, I went looking for an example of Gregory Soros’ art – and could find nothing, so his conceptual art may in fact be in calling himself a conceptual artist.) The other was Courtney Sale Ross, widow of Steve Ross (sorry, that’s Steven J. Ross), who founded Time Warner. Both, in other words, top 0,1 percenters. Matthew, while claiming to his acquaintances that he was their whizz financial advisor, was in reality their humdrum (as in go-make-me-a-sandwich) personal assistant.

But clever Matthew figured out the grift angle. He could never climb up to the 0,1% of course. Minimum price of entry is hundreds of millions of dollars. Maybe more. BUT, the asymmetry of wealth distribution, even in those top echelons, is such that cultural institutions have yet to catch up. They are willing to sell their prestige at top 1% prices, maybe even top 5% prices, even as the real wealth is intensifying in the hands of the top 0,1 or 0,01, or even 0,001%. In other words, to put it in the language of stock-jobbery finance, there’s an arbitrage play here. Matthew could steal sums of money that, on the one hand, were enough to buy him respectability through leading cultural institutions – a one-percent life – but which, at the same time, were essentially insignificant rounding errors in the wealth of his 0,1% employers.

His gift to the Frick museum has not been disclosed, but it was somewhere between $1 and 5 million. Given the size of the fortunes controlled by Soros or Ross, that is a paltry, negligible sum, like the amount of money you or I might spend on a not very nice pair of shoes. If we use Picketty’s average growth rate for capital wealth, they would earn that amount on their existing fortunes in about a week, maybe two. So for a small fraction of the wealth his employers were earning on their existing wealth, Matthew Pietras was able to lift himself into the highest echelons of New York society. I don’t mean to be bossy, but you should read that last sentence again, just to absorb its full impact.

Okay, I know you won’t do that, so let me put it another way. Matthew Pietras got his name inscribed in stone at the Frick Museum and had a position named after him there at a price tag that was, from the perspective of 0,1% wealth, so low nobody even noticed. Indeed, his grift only came to an end when, not his employers, but a banking system flagged an unusual transfer, leading to an enquiry. Within a few days a lifeless Pietras was found at his apartment.

So to my eyes, the interest in this tale is not the colourful career of an adept grifter who philanthropized his way into polite society. Rather, it is a deeper story of wealth inequality in our society. We can’t truly fathom the staggering concentrations of wealth in very few hands that our system has created. Yes, graphs and charts like the one above can tell a visually impressive story, but it’s hard to glean what exactly all that skewing to the top means. The Pietras story is that graph in telenovela format. You can join the ranks of the super-wealthy by stealing from the ultra-wealthy, and yet the amounts involved – as a function of that ultra-wealth – are so derisory, so trifling they go unnoticed. This isn’t a morality tale of a social-climbing mountebank getting his comeuppance. It’s a lesson in the economics of late-stage capitalism.

Thanks for reading, and as always, if you made it this far, throw me a like, share with a friend, and/or leave me a comment. I read ‘em all!

An illustrative tale!

Piketty's postulate from that tome is characterized as r>g, and for a while you could find nerds wearing that equation on t-shirts. But in his later work he added nuance, blaming regressive taxes, property ownership, access to education, and other factors. I think this other stuff is more interesting when we talk about wealth inequality in the US, and specifically when we implicate Musk, Zuck, et al. They are not simply stock-jobbersons, nor are they merely beneficiaries of r>g. They gamed a system that benefited from extreme versions of regressive tax and rent-seeking via lobbying and relationships. They are also de facto monopolists, which is partly due to the unique effects of building zero-marginal-cost internet companies. This reinforces Piketty's later work that claims that policy, broadly speaking, is the main problem here. I think we're now 3 decades deep in this tech monopoly grift, and those at the top have been incentivized primarily to take advantage of laws and tax regimes that still haven't caught up and probably never will.

Rolf your are the best 🔥