For the past month, a deer has been coming round to visit me every day at my cabin in the Canadian woods, parking itself under our bird feeder to feast upon seeds scattered on the ground. This deer to my inexpert eye looks to be a male yearling, probably born less than two years ago and now, having been cast out by its mother sometime last fall, facing its first winter on its own. It has been a cold winter, even for Canada, with temperatures regularly falling below -20ºC. The snow is deep, and food is scarce, and for all the animals who overwinter here, these months are a basic struggle to survive. Although he doesn’t know it, of course, I am glad this deer stumbled upon our feeder – and I have been putting out extra seed on the ground to make the winter easier for him – because his arrival coincided with the declining health of my mother, Jean B. Showalter (Strom-Olsen); and he has kept me company through her last weeks of life. She died, not unexpectedly, and peacefully, late last month. In such moments, it’s good to have a friend.

Unlike my cervine companion, whose knowledge of the maternal is shaped instinctively, and over a purely formative stage of his existence, our understanding of the maternal is emotional, enduring (hopefully), and profound. I have been revisiting my mother’s life over the last weeks in the things we all leave behind: the words she wrote, the photographs that were taken of her, the recordings made that captured her voice, and, gratefully, the sound of her laughter. As I have been visiting my mother’s life over the many decades she lived it, a great notion has been slowly taking shape in my head about the meaning of having had a mother, and how much I have gained by having had my mother. And how much I have lost.

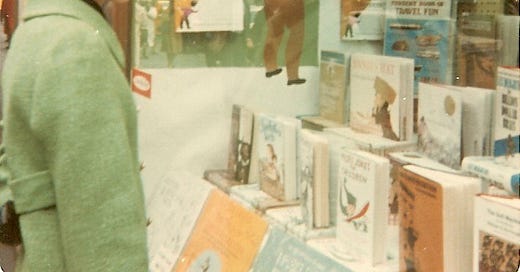

The picture above is my mother looking mid-sixties-fabulous, admiring her handiwork through the vitrine of the Doubleday Bookstore in Manhattan in 1966. She had graduated from Wellesley College a few years prior with a degree in History, and had taken a job as a secretary at the publishing house Doubleday. She was quickly promoted to the position of editor and in-house author in their children’s books division. At the time, Doubleday had bought from the famous Swiss illustrator Roger Duvoisin a series of drawings, which featured a little boy and a duck, but there was no accompanying story that connected them. My then 24-year old mother was asked to pen a text suitable for young children that wove together a narrative from these illustrations. She did, and entitled the result “Around the Corner.” You can see it here, and if you have young children I suspect you will find they are as taken with the story as many children have been over the intervening years, and as I and my sister certainly were many decades ago when we had the story read to us – by the author! – when we were little.

This picture was taken well before I existed, before she was my mother, and yet when I look at it of course I see my mom. That’s the thing about moms, I think, because, responsible for your being, and not in some narrow zygotic action of biology, but in that overwhelming sense of totality of being, it means that you can look at a picture of someone you never knew, nor could have known, at age 6 or 16 or 26, and see, feel, comprehend the person that you did know, outside of any time or place, being in the world so you could be in it too.

A poem that my mother particularly liked (and she was a great reader of poetry her whole life) was “Mr. Flood's Party” by the American poet Edward Arlington Robinson. It describes an evening in the life of Ebenezer Flood, an old man drinking hard liquor alone one autumn night above the New England town where he lived. Not a very inspiring image, perhaps, from an obscure poem by a rather mediocre poet, but she loved the poetry of the last lines, especially:

There was not much that was ahead of him,

And there was nothing in the town below—

Where strangers would have shut the many doors

That many friends had opened long ago.

Rereading the poem now, I see the things my mother liked in it – the loneliness and nostalgia, and maybe just the sense of growing old – but also something else besides. Our mothers have a special meaning for us because they make, and keep, the world familiar. And when they’re gone, we’re confronted, inexorably, with a door that long ago was opened, and now has shut. It’s what loss is.

The Deer is back. We have both, in our different ways, lost our mothers. It’s just the way things are. And come Spring, he will wander off far afield, and that’s okay. I am glad he’s here for now, because, for this Winter, we need each other.

My sincere condolences Rolf!

Thank you!