The Enschmittification of Politics

Is a German jurist who knew evil when he saw it the angry prophet of our times?

A course I teach with some frequency is an introduction to political philosophy. Because I am just too lazy to write up detailed lecture notes, I instead recorded one year a set of my lectures, and now refer back to them to refresh my memory. In a moment of what seems, in retrospect, an act of unlikely optimism (or maybe just self-delusion) I even went so far as to edit them into a set of videos and put these into a publicly available YouTube playlist, so that (this was my idea) students could consult the lectures linked to explanatory notes and thus use them as a reference when writing up their work for the course.

Now, it will come as little surprise that the views for these videos is somewhere between single and low double digits since it turns out that my students, barely able to stay awake in the actual lecture, are hardly eager to repeat the experience voluntarily. And while there may in fact be a wider public interest in a didactic lecture or two on the thought of an Aristotle or a Machiavelli, anyone interested and motivated enough to want to watch such a lecture is also going to know that I ain’t your boy for delivering sharp-eyed and clued-in observations when there are much better options available. So the project has languished in a kind of neglected obscurity, gathering internet-dust, attracting a trickle of visitors when my class is in session (and bless those few!).

However, there’s a somewhat alarming exception: a recording of a lecture I gave on the political ideas of the German philosopher and jurist Carl Schmitt, who was born in 1888. Unlike my other pedagogical videos with their view-counts in the 10s, this one is in the thousands – still well below your average video discussing different types of cat litter, but well above the average for my sad-sack little playlist.

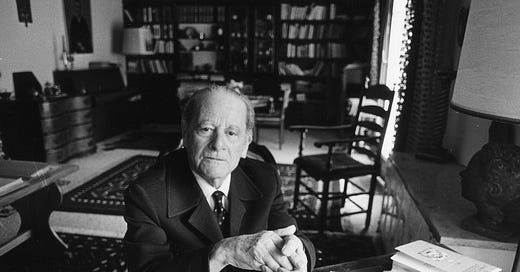

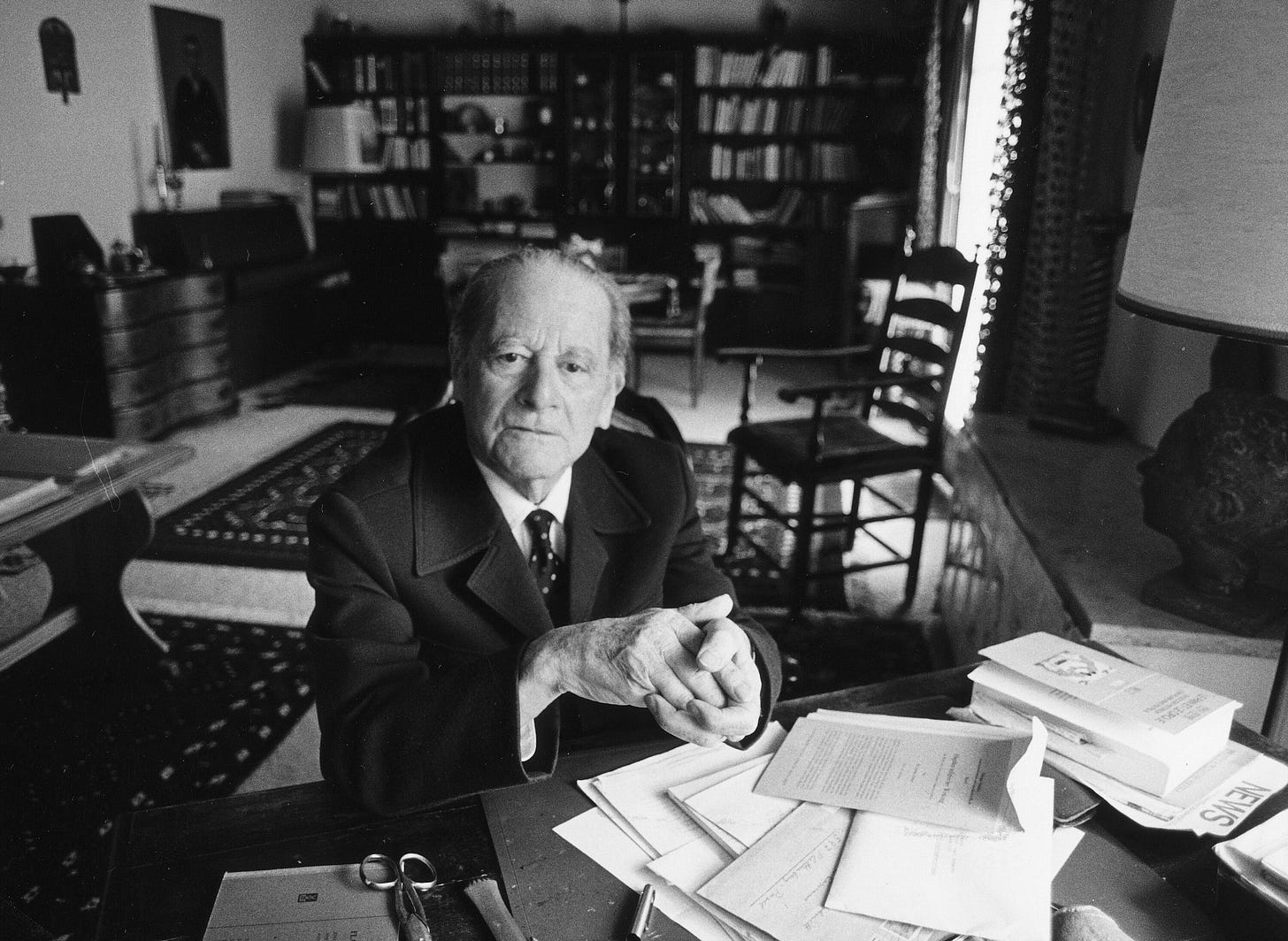

The reason? People seem attracted to the ideas of Carl Schmitt and hence are willing to sit through even the underwhelming content like the one I have up. Now if you haven’t heard of this guy, here’s why that’s an alarming thing. Carl Schmitt was a Nazi. In fact, he’s often referred to as the philosopher of Nazism. He enthusiastically joined the party after Hitler rose to power, he vigorously espoused the most vicious of its racist and anti-Jewish postures through the 1930s, and he offered intellectual succour and support to the Nazi state for the duration of its existence. Even worse (wait, can it get worse you ask? oh yes, it can), after the War, he steadfastly refused to renounce his support for Nazism, and remained therefore outside the margins of polite, respectable and, you know, not Nazi, circles for the remainder of what would prove to be a very, very long life – proof, perhaps, that single-mindedness, stubbornness, and unwavering convictions that you are right and everyone else is wrong can be good for your health, if bad for your ability to be part of civilized society. He lived to be 95, dying in 1985.

Now, when people like me talk about Carl Schmitt, it is almost obligatory to offer up lots of prefatory mea culpas for engaging with his ideas. But in that particular video, I forgot to press the record button until after I had extensively deplored his career and offered up the necessary qualifiers about how awful he was as a person, so any rando stumbling across the video will encounter a seemingly disinterested, if not very intelligent, account of his views. This may explain its relative success, if such it could be called.

As I have been watching with increasing dismay the state of political discourse over the years, it strikes me that Carl Schmitt is, in intellectual terms, having a moment, one that is very modestly reflected in the wider interest in that particular video. I have always found it hard to capture the essence of Schmitt’s political thinking, although there are some basic ideas that are easy enough to express, which I will get to in a moment. But I have always been of the view that to understand why Schmitt thought the way he did, and remained unwaveringly committed to these ideas even after the consequences of his view of the state had produced unprecedented atrocities and left his own country in literal ruins, was his profound commitment to a Catholic understanding of the world. And by that I mean not just that he was a believing Catholic, but rather that he had a kind of deep-seated, apocalyptic Catholicism coursing through his veins. In Schmitt’s ideal world, we would be able to return to some kind of mediaeval, or at the very least aggressively non-modern, political configuration, where power and authority is entrusted to the right institution – the right institution being the Catholic Church, which was, in his view, the only transcendentally rational force in human history, steering folks away from evil and guiding them to their own salvation.

This is not a very blistering insight, considering he wrote book entitled Roman Catholicism and Political Form. But Schmitt, born Catholic in Westphalia, was actually excommunicated from the Church in 1926, which I think ironically only deepened his commitment to his Catholic views, since it demonstrated to him (and I’m just guessing here) that the scourge of modernity had wrecked even this once-noble institution.

At any event, when Carl Schmitt woke up each day he saw a world in which there was the real presence of good and evil. And that evil made itself manifest in the world as modernity itself. The materialist foundations of industrial economies, and the accompanying political arrangements – which we know as little things like, you know, parliamentary democracy and constitutional liberalism – this was the devil at work. So he ended up formulating in his political and juridical philosophy a kind of remedial atavism that could thereby rescue the depraved and wicked (i.e. all mankind) from the tools of their depravity and wickedness, like universal political rights and individual subjective expression. As he put it in his work, Political Romanticism, “in this society, it is left to the private individual to be his own priest. But not only that. Because of the central significance and consistency of the religious it is also left to him to be his own poet, his own philosopher, his own king, and his own master-builder in the Cathedral of his personality.”

One way of reading Schmitt’s work is that the modernity unfolding around him had dangerously distracted people away from the proper spiritual business of their lives with flashy commodities, mindless entertainments (no Swiftie, Carl Schmitt), and illusory political institutions that suggested people can exercise sovereignty over themselves and in their own way. Schmitt’s response to the establishment of the Weimar Republic in 1919, which established a modern Federated, democratic, parliamentary state in Germany for the first time in its history, was to write up a pamphlet entitled Die Diktatur (On Dictatorship), which, to be clear, is a hearty approval of dictatorship, and a kind of political-philosophical fuck you to the idea of political autonomy and self-determination at the level of sovereign authority. Different political parties bickering about policy might work as long as the stakes were suitably minimal, like deciding on the right tariff-levels for imported milk from Denmark. But when real decisions had to be made, like dealing with foreign threats, the very format of a parliamentary republic could lead only to chaos, so the solution had to be the imposition of dictatorial powers to restore – and you have to appreciate the breathtaking irony here – the rule of law. It was this line of reasoning that made him an excited proponent of Hitler’s dictatorship.

This way of seeing the world eventually led Schmitt to a famous formulation which opens his short work entitled Political Theology: “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” According to Schmitt, the great menace of modernity was that it had enshrined the idea of a sovereignty that lay with the people, where that popular sovereignty could be meaningfully expressed through pluralist, representative, and open institutions, buttressed by judicial review and free discussion. Schmitt saw that idea as absolute bullshit, since it replaced true, transcendental sovereignty (God, basically, and His institution the Church, as it used to be) with the nice-sounding, but ultimately illusory and dangerous idea of sovereign immanence (i.e. from within the self). The complete insanity of this idea, for Schmitt, could best be seen during moments when there was some kind of emergency, or, as he put it, “the exception.” In such moments, a true sovereign power must emerge, kind of like a driving instructor grabbing the wheel as some hapless 18-year old is about to veer into oncoming traffic.

Liberal constitutionalists, Schmitt believed, were willfully naïve. They had unreasonable confidence in the technical workings of liberal constitutionalism’s institutional apparatus to solve the great problems of the state, whereas such moments were precisely when real power had to emerge to defend or, as needed, restore law and order.

As such, modernity, and modern politics especially, was a kind of self-indulgent fever dream, raving, delusional, and vulnerable. Writing in the 1920s, Schmitt was especially appalled that the only people who seemed to understand the true nature of power were the goddamned Marxists, what with their “dictatorship of the proletariat” in control of the “total state” to usher in, eventually, a stateless, collective, commodity-driven, Godless hellscape of intensely-material prosperity and social equality. Fuckers.

Worse yet, people who live under the illusory autonomy of a liberal constitutional state become unwitting but active participants in their own self-destruction. Power, that is the power we need to assert truth and rectitude, becomes anonymous, embedded inside opaque institutions, like judiciaries, or state assemblies, issuing cryptic pronouncements on all matter of administrative minutiae, stripping power of its meaning and effect, plunging Joe and Jane Citizen into a kind of ignorant political alienation. But since the political is encompassing of all elements of the self (in Schmitt’s calculation), this is actually a form of total self-alienation. Instead of being decisive moral actors, we become numbed by an administrative and bureaucratic culture which essentially dissolves our political autonomy in the fiction of “constitutional liberties” and representative political regimes.

The resolution to this quandary was for the sheeple to wake up to a fundamental reality: people who didn’t think like you politically were not just folks with whom one might engage in spirited but civil discourse to arrive at a congenial and consensual meeting of minds. No, they were the enemy. As he put it in a famous phrase, “the specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy.” And that friend/enemy dualism was actually just another facet of the ultimate duality inside human society: good versus evil. The arch-Catholic, hyper-conservative Schmitt, looking around in the 1920s, saw plenty of enemies: Marxists, Socialists, Liberals, Reformers, Free Thinkers, Decadents, Degenerates, and, of course, Jews – always Jews.

It was just romantic irrationality – and Schmitt loathed Romanticism – that one might find common ground with those who disagreed with you by, say, celebrating a shared ardour for the grandeur and beauty of the human spirit, our capacity to live, love, laugh, and delight in the same natural world in which we all live. Fuck that. These people were enemies who needed to be hated, and hard. How do you treat your enemy? You don’t invite them in to resolve your differences over a beer. That’s for witless, know-nothing, beta cuck sophead shits. Instead, you recognize that these people represent an existential threat, and you act toward them as you would any enemy. No quarter given; they either change their ways or else you eliminate the threat they represent.

Let’s do a little Schmittian math. If (1) real sovereignty needs to emerge during “the exception; and ” (2) “the exception” means facing enemies who are intent upon your destruction; and (3) the political is about recognizing that the people who disagree with you are, in fact, the enemy; then, (4) politics is always exceptional and the absurd fiction of liberal constitutionalism as a viable political arrangement is exposed for the complete sham that it is.

Now, if you have made it this far, I invite you to look at the way politics is unfolding around us. One way to make sense of our shitty politics is to recognize that it is simply Schmitty politics. In the 1990s, US Republicans tried to impeach then-president Bill Clinton for oral indulgences he received at work and his subsequent mendacity, arguing that this effort to cover up his indiscretions was a threat to the rule of law. I mean, it was a simpler time.

Consider how Schmittified the discourse has become over the decades since. Move aside furtive blowjobs. Now, we have your political opponents salivating at the prospect of hordes of illegals – many of whom are criminals, reprobates, and the insane – to overwhelm your country, seize your house, take away your job, steal your money, eat your cats and dogs, assault your women, and turn the whole state into an unliveable shithole. That is the line coming out of, not just the US right, but many other places as well. And a politically successful line it is. The Rassemblement National in France, for example, stresses uncontrolled immigration as an existential threat to France, aided by shilly-shally, virtue-signalling, radical leftwing, idiot wokesters whose main point of identity is they just hate France so much. Ditto the German right; ditto the Austrian right. Even here in Spain, where I write these words. Find a modern post-industrial society that doesn’t have this kind of politics. Doesn’t exist.

So, too, these conservatives’ idea of a deep state, one embedded inside liberal constitutionalism, that deploys and weaponizes a dehumanizing scientism: promoting vaccines, or policies to fight climate change, or universal educational standards, so that your fundamental autonomy to get sick from measles, or drive an SUV, or tell your kids what and how to think is stripped away from you. From the perspective of this right wing discourse, these people already hate you. They are the elites that have contempt for you, who belittle and diminish you, who think you are deplorable, an obstacle to progress, modernity, and their insidious plan to universalize the shit out of everything and take away your core identity.

Now you have to hate them back.

In other words, these right wing parties are now defining what is a growing part of the political spectrum in clear Schmittian terms, one that recognizes the best political line of attack is to present everything as an emergency, as the exception, and the people who disagree with you as intractable enemies to be despised. LGBTQ+ rights? Emergency. Calls for a green economy? Emergency. Modern women living modern lives, aka childless cat ladies? Emergency.

It all makes much more sense when you come to the viewpoint that positions, policies and priorities expressed by your political opponents represent the hateful propaganda of an enemy intent upon destroying you, your way of life, your identity, everything, in other words, that actually defines your sovereignty. And unlike the old communist bugbears of yore, this enemy is fostered, nourished and armed from within. The state and the fight for its control thus becomes the site for an existential struggle.

With even a modicum of perspective, it is jarring to realize that there are hundreds of millions of people across the developed world, people who enjoy the highest-ever level of human prosperity ever experienced, not only in terms of material comfort, but also in terms of well-being – life expectancy, access to education, good health, etc… – who are nonetheless eager consumers of a political invective that stresses their lives are terrible, that everything they cherish is under threat, that the way of life they care about is on the cusp of being destroyed – and forever – by their political enemies, and until they start learning how to hate back extra hard they will be condemned to a political oblivion in which all they are and represent will become unrecognizable and extinguished by forces at once self-righteous, condescending and deeply immoral. And it is worth pointing out that the one thing that truly does pose an existential threat to their way of life – climate change – they are largely convinced is either a greatly exaggerated left-wing con job or an outright hoax. Science – fuck that.

All this would have made sense, I think, to Schmitt. He died at the very end of the Cold War, which did much to elevate liberal constitutionalism, political pluralism, and the idea of an open society as a universal political virtue. He must have died mad. But man, he’d be feeling better these days! I am sure that Schmitt would have completely allied himself with the “make-great-again” discourse, as long as it was referencing some distant past where God and Church (and not the bullshit evangelical kind, but the proper Catholic kind) were the organizing aesthetic and political principle.

Schmitt’s thinking was a symptom of his time – the 1920s, when the perception of a society in chaos was widespread. Little wonder then that there’s a general anguish amongst those who, gamely operating within the normative assumptions of liberal constitutional democracies, sense a resurgent sympathy for fascism. Schmitt’s “political theology” is back, baby! And so what and who cares if the prophets of this political theology cavort with porn stars or sidle up to authoritarian strongmen or hand out cash to their cronies. The other side is, always has been, and always will be, worse. You don’t talk with them, you can’t reason with them, and you certainly shouldn’t feel any empathy for them. You just need to defeat them before they defeat you.

Schmitt knew this. And look how well it worked out for him and his country. Happy times.

Although it seems like there is a mastermind behind this distrust in democracy, the emergence of populist far right leaders is, ironically, a product of democracy itself. The likes of Trump are people that have nothing but the ability to read the cries of the voters. I wonder if the left is looking for ways to not be responsible at all for what is happening and sadly it takes two to tango.

Whilst I try to comprehend the tmindset of the 1920s and 1930s, it is difficult to grasp from reading alone. What I am witnessing in social and political discource now is highly concerning, the respectful policy disgreements appear to have vanished and abuse is now the norm. The concern is one hundred years later, we appear to have learned nothing.