The Impossible Exam vs. the Machine (Part 1)

I fed Chat GPT my "impossible MBA exam" and the results were ... interesting

The course I used to teach (CMT) was locally infamous for having a final exam that students widely considered to be an exercise in professorial tyranny, bordering on a kind of pedagogical sadism. Students could be seen after having suffered the ordeal wandering about dazed and baffled by the whole experience. I can recall distinctly running into a student who had just taken it who asked me, not with aggression, but rather with genuine confusion, “what the fuck was that?” He spoke for many.

Now as we all know, we seem to be upon the cusp of a major shift to a new plateau of AI-enabled learning and output after the introduction last fall of the widely heralded tool, Chat GPT.

What would happen if I fed this “absurd” (not my term) exam into the AI chat? That was the ingenious suggestion of one victim of the exam, the inimitable Alex V., friend of the ‘stack and apparently major dance floor sensation. Very good idea! So, I decided to pull up the new AI tool GPS Chat and give it questions from my exam. The results were both unexpected and illuminating.

Now before considering the results, I should outline briefly the infamy of the exam itself (with apologies for provoking any PTSD or flashbacks amongst some of my readers). The exam was indeed somewhat fiendish, but not because I have some inherent desire to torture students (my lectures suffice for scratching that itch). Instead, I, like many professors, faced a logistical and ethical issue when students took the final exam: how to avoid cheating, whether through collaboration, or using online resources, etc…. The normal approach is to have everyone assemble in a classroom and eliminate the possibility of cheating by having a close monitoring of the room. The problem that I faced with this approach was that, with many different sections taking the exam at different times, there was a real possibility that questions might be “leaked” from one group to another based on when they took the exam. So, I opted instead to make a “cheat-proof” exam. This meant they could take the exam outside of the classroom, in any setting they wished during a specified, typically 12 hour window. As a result, no behaviour or strategy was forbidden. Collaborate? Sure. Check/share your notes? Please. Feverishly look online for answers? Absolutely! Prayer or, even better, mind-enhancing substances? Go for it. In short, I tried to craft an exam that could withstand whatever attempt to game the system was employed.

How, you might ask? Well, here’s an example:

“Which of the following best explains why Steve Jobs' departure from Apple in 2011 was cheered by investors and led to a sharp increase in the company's market valuation?”

The background to this question is the fact that after Steve Jobs left Apple (shortly before his untimely death from Pancreatic cancer), the share price of the company rapidly increased, despite widespread acknowledgment that he was integral to Apple’s success. So prima facie the market reaction made no sense. Wouldn’t the share price decline after losing its visionary-in-chief? Well, not in a world of shareholder primacy. Jobs had notoriously refused to distribute any of Apple’s enormous mountain of cash to the shareholders and was indifferent to driving up the share price. His moral authority over the company he’d founded meant it was difficult to overcome this obstinacy. So with Jobs out of the way, investors (rightly) concluded that the company would become more responsive to shareholder interests. This was discussed in class. Now, here are the possible answers:

a) Jobs' indifference to investor interests meant that the company was likely to issue dividends only after his departure.

b) Jobs' refusal during his tenure at Apple to distribute capital to shareholders meant the company had accumulated very significant cash reserves that could be used to reward shareholders after he had stepped down.

c) Jobs' indifference to Apple's share price meant that the company's capital position would likely ameliorate after his departure.

d) The senior management team after Jobs' departure was seen as more favourable to shareholder interests.

All the answers, with the exception of (c) – since Apple already had an enviable capital position – appear to be correct. But you need to choose the best answer. To do that, you have to use some rather subtle reasoning to conclude that, of the possible answers, the best answer is … option (b). Answers (a) and (d) are both generally correct, but while they might explain why Apple’s share price would retain investor support, only answer (b) with its emphasis on “very significant cash reserves” links clearly to the “sharp increase” noted in the question. So you can be sitting in a group, or checking the web, but in the end you have to reason out the answer. I should also note the exam was time limited, and had a large question bank from which 20 questions were drawn randomly, so the odds of any two people having the same question at the same time were extremely low. In other words, the idea here is that, independent of how, where, or with whom one took the exam, it would inevitably require an individual’s own (not inconsiderable) effort to get the right answer.

I had many questions of this type – plenty of generally right answers, where nuance and deeper thinking were required to work out the best answer. One consequence of this approach was that no-one ever scored a perfect grade on the exam – indeed a “top” score was typically 75%. A score of 85% happened only once or twice across its dark and ignominious history. The overall distribution was almost always perfectly Gaussian, with both the average and median grade somewhere between 48 and 54%.

So, back to the topic at hand, how would ChatGPT do when faced with the challenge of using nuanced (human) reasoning to arrive at the best correct answer. Instinctively, both Alex and I thought it would have a hard time making these fine-edged distinctions, and so would suffer a similar fate as my unlucky students.

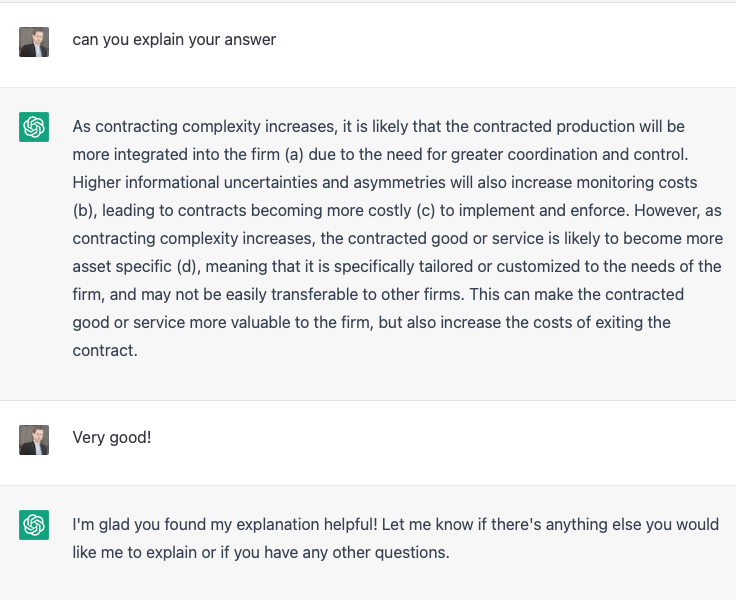

Well, here’s how it answered that particular question, complete with an explanation (when prompted):

Impressive! The right answer, and clearly for the right reason, with its emphasis on maximizing shareholder value correlated to the “accumulation of significant cash reserves.” I checked the last time I set this question to actual people, and – there were no correct answers. Everyone chose (d), which is indeed highly plausible, but not the best answer.

***UPDATE***

At the insightful suggestion of a reader (my old school pal Ray), I asked if the Chat AI could explain why this was the best answer. Again, its logic was clear and perspicuous:

Solid and unimpeachable reasoning!

* * *

Here’s another one. In my class, I stressed the role that stock options have played in grossly inflating executive compensation and distorting firm strategies to produce more favourable outcomes to short-term shareholder interests, which explains the choices for this question:

All of these answers are, again, generally correct, except for the causation (not to mention grammatical mistake) in (d), which is highly disputable (although some would maintain this is true). The best answer, though, is (b) since it clearly links to the alignment of executive and shareholder interests (via the issuance of options and restricted shares).

How did ChatGPT do?

Right again!

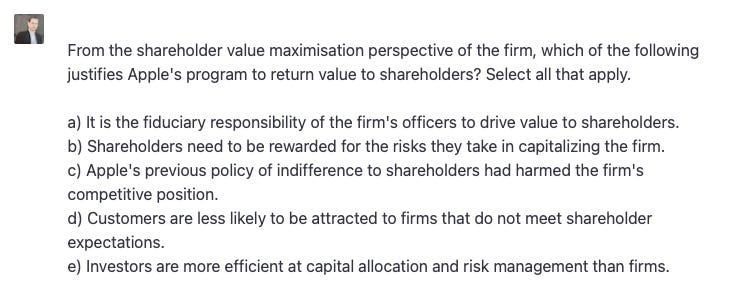

On basic questions of firm theory (of which my exam had plenty), the AI came up aces.

Indeed, since contracting complexity and asset specificity are in positive correlation. But could it explain its answer? I checked.

That’s a perfect explanation; I couldn't have said it better myself.

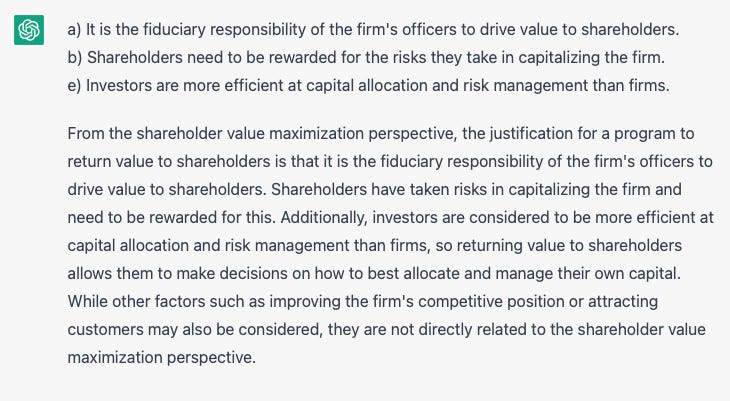

In the following question, students performed well enough, but in very few instances did they get the full array of correct answers. Here it is:

Most students got that answers (a) and (b) were right (at least according to the theory). But there’s an additional correct answer. The AI nosed it out.

Exactly. Shareholder value theory holds that firms should not hold on to surplus capital as it is market inefficient. Since this argument is exogenous to the firm itself, it requires a subtlety of thinking to realise it is also a correct answer.

Next, turning to a question that almost all people got wrong, produced a very interesting exchange when I challenged the AI on its logic.

So prompted, ChatGPT reconsidered as follows:

And that is, indeed, the correct answer. (Interestingly, students also typically selected “all of the above,” like the AI´s initial choice).

Let me conclude with the following interesting exchange, which suggests the AI is not perhaps as passive in accepting professorial nudges as the above exchange might suggest. I copied this to text, so you’ll have to take my word as to its veracity.

Me:

Which of the following are examples of opportunism? Select all that apply (up to a maximum of 3).

a) Free-riding on team projects.

b) Shirking responsibilities.

c) Seeking to maximise a bonus payout by working weekends.

d) Colluding with others to remove an under-performing team member.

e) Reporting unethical behaviour to senior management.

f) Withholding cooperation on a team project.

Chat GPT:

a) Free-riding on team projects.

b) Shirking responsibilities.

d) Colluding with others to remove an under-performing team member.

f) Withholding cooperation on a team project.

Answers (a), (b) and (f) are indeed correct. But, in my view, (d) is not correct, since opportunism means an action that brings individual benefit, whereas (d) describes a behaviour that brings benefits to a group (against an individual). This produced the following exchange:

Me

Why is collusion with others to remove an underperforming team member an example of opportunism?

Chat GPT

Collusion with others to remove an underperforming team member can be considered an example of opportunism because it involves working with others to achieve a personal benefit, in this case, the removal of a team member who is perceived as not pulling their weight, which may make the remaining team members' workload easier, or increase the chance of success for the team as a whole. Additionally, it can be considered as an unethical behavior, as it is not a fair way to deal with underperformance. It also undermines the principles of teamwork and mutual accountability.

Me

But the personal benefit is attenuated by its being shared broadly with other members of the team. Is that really opportunism?

Chat GPT

You are correct that when the personal benefit is shared broadly among the team members, it is not as clear-cut an example of opportunism as when the benefit is gained solely by one individual. However, collusion to remove an underperforming team member can still be considered opportunistic behavior because it involves working with others in order to achieve a personal benefit, even if that benefit is shared among the team. Additionally, the action is not fair to the underperforming team member, and it might break the principles of fair play, accountability, and can damage the team dynamics.

Me

But unfairness is not necessarily a result of opportunistic behaviour, correct? Whereas opportunism is always a matter of personal benefit at the expense of others. In cases where that benefit is shared by a large number of people as opposed to just yourself, do you still think that should be considered as opportunistic behaviour?

Chat GPT

You are correct that unfairness is not a necessary component of opportunistic behavior, as opportunism is primarily defined as the pursuit of personal gain at the expense of others. However, in some cases, the pursuit of personal gain can also be unfair to others.

In the example of collusion to remove an underperforming team member, the benefit of having one less team member to carry the workload is shared among the remaining team members, but the action is still considered as opportunistic because it is driven by the desire for personal benefit, rather than by a fair and objective assessment of the team member's performance. Additionally, it can be considered as unethical as it undermines the principles of teamwork and mutual accountability.

In general, whether or not a behavior is considered opportunistic depends on the specific context and the motives of the individuals involved. It is important to evaluate the behavior in the context of the situation and consider if the individuals involved are acting primarily in their own self-interest, rather than in the best interest of the group or organization.

Me

I think you are wrong to assess that, in general, answer (d) is an example of an opportunistic behaviour.

Chat GPT

In the example of collusion to remove an underperforming team member, the action may or may not be considered opportunistic depending on the specific context and the motives of the individuals involved. If the team members are motivated by a genuine concern for the team's performance and the underperforming team member is given an opportunity to improve and their performance does not improve, then the decision may be reasonable and not considered as opportunistic behaviour. But if the team members are motivated by personal gain or the underperforming team member is not given a fair chance to improve, then it can be considered as opportunistic behavior.

It is important to evaluate the behavior in the context of the situation and consider the motives of the individuals involved, whether they are acting in their own self-interest or in the best interest of the group or organization.

So, in this case, the AI refused to accept my pronouncement, and (very politely) stuck to its guns. While I don’t think the AI is correct, since “collusion” implies that you are acting in a group context outside of immediate narrow self-interest, its reasoning is fair. So perhaps this suggests my question was not especially well-expressed.

In part 2, I’ll post some other interesting exchanges and a few tentative observations about this interesting experiment. Like, how worried (or is it impressed) should we be? Meanwhile, many thanks to Alex for the idea!

Not so impossible according to AI, pretty impressive programming. I wonder if it calculates all of the supporting points/views before its answer, or only after you probe it for more explanation.

Alas, I was not the Alex that made the suggestion, but kudos to my counterpart. This brings back fond memories of arguably my favourite test I've ever taken, largely because I relish logic problems, and not in small part because it was done while drinking wine with a cheese and jamón platter.

However, I'd have to agree that the last question could benefit from reworking. Opportunism is purely acting for one's own benefit by seizing an opportunity when it arises. While it usually includes an element of surprise or randomness, and perhaps some guile and moral flexibility, it does not strictly preclude working for that benefit, as work is just another word for consistently taking action. Elaborate schemes to realise a self-benefiting opportunity could easily be considered work.

Hence my answer would be A, C and D, however D is subjective, not for the reasons outlined above (although I see the merit), but because you would have to prove that underperforming would have to equate with destructive. It would not make sense to remove a team member that is doing some work, but just not as much as everyone else, since removing them would create more work, not less. So if they could be replaced with a well-performing team member, or their removal in some way meant a significantly better grade/outcome that offset the loss of productivity, then I agree with ChatGPT that it becomes opportunistic, albeit for different reasons.

I would therefore also argue that B is incorrect, because shirking responsibilities only optimises a specific type of outcome - not doing work in the short-term. However I am of the view (and have the experience) that shirking responsibilities generally correlates with a net loss because responsibilities are usually important activities that are in some way beneficial to the doer, even if only in that they help avoid negative consequences.

Similarly I'd argue F is not correct, although perhaps very slightly debatable, because withholding cooperation from a team project is not the same as not contributing to a team project. It is more an action similar to running interference. It would most likely create inefficiencies that would make the whole less effective than the sum of the parts or even of the remaining parts. Assuming reasonably competent team members, opportunism would be just not contributing. The team will carry you to a decent grade and you'll get to slack off entirely. By this logic, F is not an example of opportunism, unless you're in a situation whereby you can ensure personal success by dragging down the group. An example would be if you're in a group with fellow students and you're all competing for the top spot in class, but they require success on a minor group project whereas you do not because you've already aced Rolf's exam ;) There'd have to be some additional factors here but you get the idea.

Hehehe, this was fun. Also a fantastic exploration of ChatGPT's capabilities. Thanks Rolf!

ps: the only consistent definitions for opportunism I can find quickly are that it requires seeking personal benefit without concern over the consequences for anyone else - but nothing says the consequences have to be negative. It is primarily a selfish action, not a nefarious one.