Things Run AMOC

Yes, things are bad. But take some solace in the fact that they'll get worse.

There’s an old line from The Simpsons that’s stuck with me over the years: an old jazz player tells a disappointed Lisa Simpson who’s playing blues on her saxophone to try to make herself feel better: “the blues isn’t about making you feeling better, it’s about making other people feel worse.” In the spirit, if not the letter, of that sentiment, one way to deal with bad things happening is to focus on worse things happening. Admittedly, that’s not especially healthy, but trust me, it works. And so, given the clown show that is about to descend upon us over the next four years, I have been psychologically medicating by dwelling on the fact that, as deeply miserable the reality of Trump’s victory is, it is simply a dismal point on a much larger and more depressing continuum.

To wit, I have been focusing of late on the imminent collapse of the AMOC. Not a very salubrious topic, I confess, but at least it serves to put into some perspective, and even garner haven from, the endless dreariness of current politics. Somehow that realization makes me feel marginally better.

AMOC is an acronym for the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. It is popularly conflated with the Gulf Stream, which is not actually part of the AMOC, but instead a parallel circulation system of surface currents that move warm water northward out of the Gulf of Mexico into the Northeast Atlantic. While the Gulf Stream is generally thought of as the heat conveyor that makes Northern Europe a comfortable place to live and prevents the Eastern Seaboard from boiling, this is erroneous. What matters in terms of heat transfer is the temperature difference in the circulation system. While the Gulf Stream does move warm water northward, that water remains at the surface and does not shed a significant part of its heat load. The AMOC, on the other hand, is a much larger system measured by water flow, and because the roundtrip involves water sinking to very significant depths (where it is very cold), the overall heat transfer effect is correspondingly much greater. Stefan Rahmstorf, the leading authority on the AMOC points out, “for climate impact, the AMOC is the big deal, not the Gulf Stream.”

People have been talking about the AMOC shutting down for years now, so this is nothing new. In fact, the AMOC shutdown was memorably captured in a scandalously scientifically-louche film entitled The Day After Tomorrow, in which the Eastern Seaboard is plunged – overnight – into a cold so deep that carbon dioxide freezes (about -80º C). Everything about that movie is grossly, laughably inaccurate. But one thing about it that is not entirely unscientific is the idea that the AMOC can shut down quickly. Not overnight, of course, but much faster than climate models had thought possible until quite recently. It is now generally thought that the AMOC is a much more sensitive system than had previously been believed.

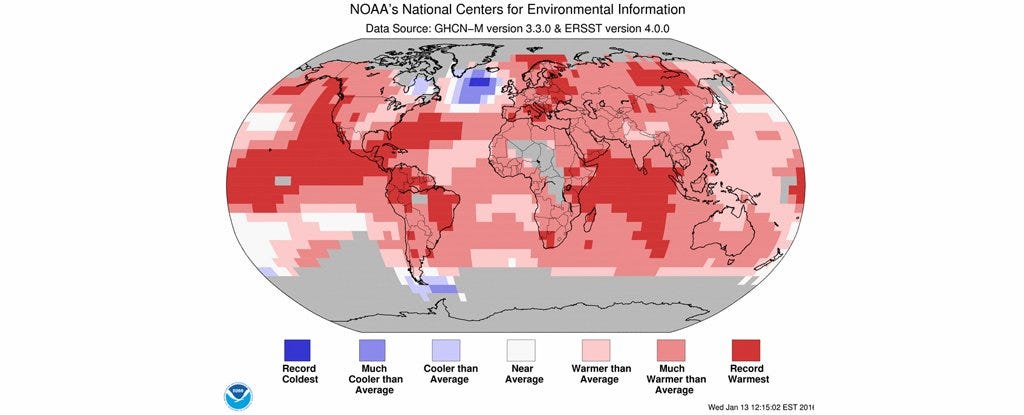

The reason the scientific consensus has changed is that we can actually see the first signs of the AMOC’s collapse happening right now, if you look in the right place. The right place has a name: the North Atlantic Cold Blob (that is, indeed, its actual name), a patch of water in the North Atlantic that is basically the only part of the world where average temperatures have not been getting warmer. To wit:

That patch of blue in the Eastern North Atlantic is exactly where one would expect to see a cooling effect if the heat transfer from the circulation of warmer tropical waters is in the process of slowing. And it is not just the Cold Blob which provides clear evidence that bad things are happening to the AMOC. Since the heat that would ordinarily be transferred to the Northern Atlantic is now remaining in more southern latitudes, one can look for increasing ocean temperatures at the southern end of the current. And that, too, is what we are seeing: off the Eastern Seaboard, the ocean is warming.

No-one (reasonable) disputes these findings, which means in sum that the AMOC system has been slowing over the last several decades. I won’t bother going into the physics of the AMOC, because you can watch the soft-spoken Herr Dr. Rahmstorf explain everything much better than I can in any number of talks that he has been giving lately. (Here’s one from the Potsdam Institute from last month). I usually just post these links as kind of courtesy for the occasionally interested reader, but I urge you to watch his presentation. It is eye-opening. And you’ll also learn how to drop the term “Stommel Bifurcation” into casual conversation. (And to think my sister says this stack brings little of value….)

Anyway, beyond the havoc that the slowing and eventual collapse of the AMOC will bring to the globe (in three words, lots of havoc), there are two serious issues raised by the emergence of the North Atlantic Cold Blob and Eastern Seaboard warming. The first is that it provides further evidence that the climate models that we have been using to chart the scale of global warming are significantly underestimating the actual effects, as we are now able to measure them. As Professor Rahmstorf points out, the standard climate models fail to predict the observed cold blob, which suggests in turn that they are very likely underestimating the overall effect of global warming more generally. That’s bad.

Rather worse is that the pace of change is happening much, much faster than anyone (other than the doomiest of doomsayers) thought was possible, even a few years ago. And the reason for that is, again, that the models we have been relying upon turn out to have been based on a set of assumptions which, it is now clear, were highly, I would say recklessly, conservative. As I covered in one of my first posts on this stack, the sensitivity of the earth’s climate system to surplus heat is turning out to be much greater than we thought, which means that much of our talk about 1.5 degrees this, and 2.0 degrees that, and carbon budgets, and all the rest of it is predicated on a flawed premise.

In short, things are bad, they’re getting worse, and they’re getting worse faster and at greater scale than is generally understood.

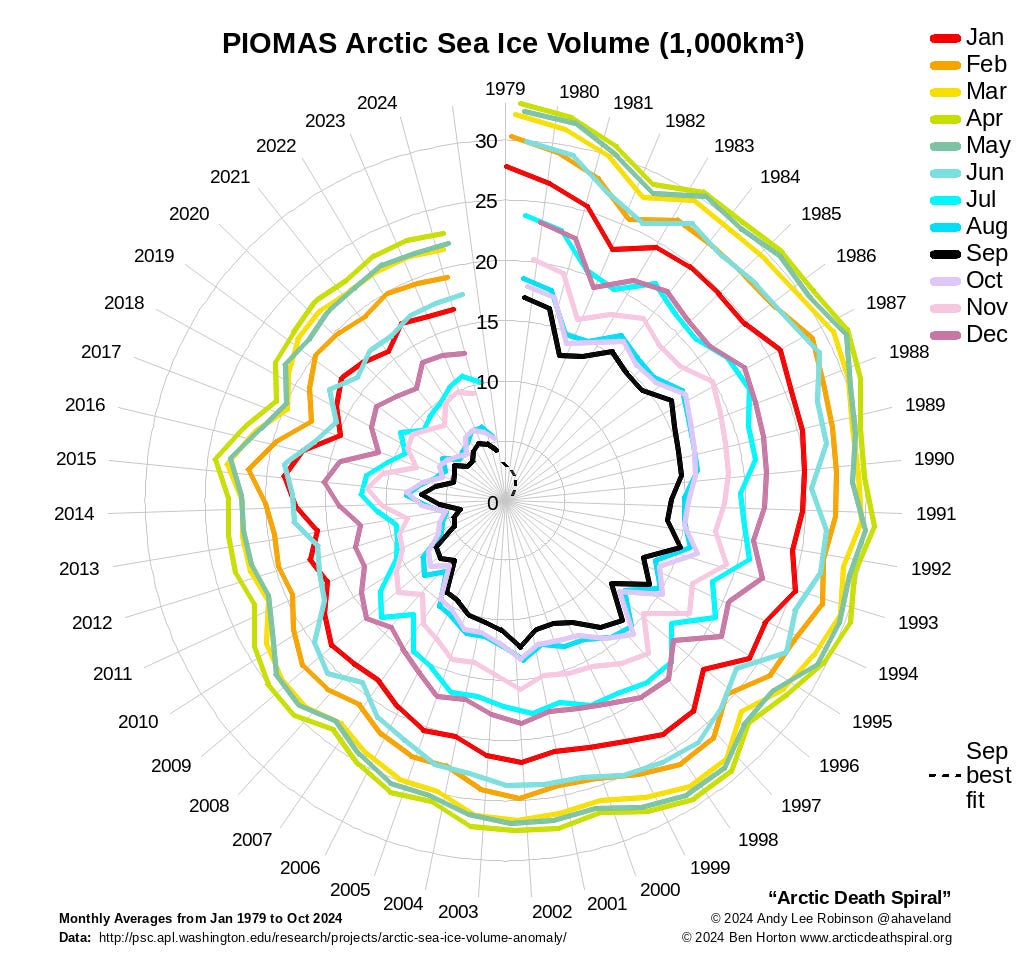

The AMOC is just one of many systems that is moving toward an irreversible tipping point. Another is the loss of Arctic sea ice – a personal favourite, thanks to the Arctic Death Spiral graphic, which is a great example of how data presentation matters. Check it out:

Just as we are watching in real time the AMOC lurching towards collapse, so too can we extrapolate to conclude that any number of tipping points are being approached much faster than we thought, and with consequences that are likely far graver than we have been imagining. If you are under 50, you will almost certainly live to see some of them.

This is not the first time the AMOC has collapsed. Interestingly, it was the collapse of the AMOC about 12,000 years ago that seems to have contributed to the Neolithic Revolution, albeit in ways that no-one has quite figured out. The so-called Younger Dryas phase of cooling coincided with the rise of proto-agricultural and proto-sedentary communities, from which sprang (eventually) a new phase of human experience that we label “civilization.” So the fact that you are reading this post surrounded by the modern comforts that civilization has produced is thanks, in an admittedly attenuated sort of way, to the shutdown of the AMOC.

I find a kind of satisfying irony in the fact that the shutdown of the AMOC twelve millennia ago led to a civilizational outcome that has produced another shutdown of the AMOC. Although the consequences of its collapse will be pretty horrific - much colder winters in Europe, and rapidly rising sea levels and concentrated storm activity in Eastern North America, plus a whole host of other things that will make life generally harder, you have to concede that there is a symmetry in the closing of that particular circle which offers a certain satisfaction.

That’s called taking the long view, folks, which is one way, at least, to deal with the clownish turmoil that we’re going to have to sit through the next four years. Feel worse yet?

Thanks for reading, and while this post is, like Kale or Mel Gibson, not especially likeable, throw me a like anyway if you’ve made it this far, and feel free to share your thoughts.

Who is doing the best science/writing on the secondary effects part: "much colder winters in Europe, and rapidly rising sea levels and concentrated storm activity in Eastern North America, plus a whole host of other things that will make life generally harder"? What is the "host of other things"?