A Lonelier Planet (Part 1)

What will it look like for our youth as rapidly rising temperatures collide with rapidly falling populations? Part 1 of a series on the convergence of climate and demographic change.

This series of posts explores the convergence of two trends that have already begun to happen and will have an increasing effect on people’s lives going forward. Someone born this year will spend their senescence in the 22nd century, by which point the circumstances of their lives will be greatly affected by two deep-seated, unstoppable trends: a planet that is both warmer and lonelier. What will this look like?

You can find the subsequent posts in this series here: Part 2 & Part 3

Earlier this year, I wrote about the Dutch elections, noting the intractable contradiction that lurks behind the recent results after (an admittedly minority of) Dutch voters backed the party of proud anti-Muslim xenophobe Geert Wilders, whose only political issue of any substance is an unflinching opposition to immigration. The contradiction is that The Netherlands, like every other developed country around the world, has a collapsing fertility rate and is facing a rapidly aging population; the only fallback it has to support its existing social system is to import a youth that Dutch people are not creating the old-fashioned way. (This assumes that forced procreation is off the table, although with Geert you never know….) By backing Wilders’ party, so I suggested, Dutch voters were, in essence, putting their heads in the sand. And before you start laughing at short-sighted Dutch people, I remind you that pretty much every developed country is already facing or beginning to face serious political problems around the question of immigrants. And I am not just talking about hyped-up National Front supporters or all those freaked-out Americans who woke up in 2008 to discover, “OMG Mexicans are everywhere!” but even countries with more decent and welcoming policies like, oh, Canada, Norway, or … Australia? Okay, probably not Australia, but you get my drift. So smirk not dear reader.

Anyway, I’ve been dwelling on this issue for some time now. Students from my now-defunct management class (or those, at least, who stayed awake AND listened – not so many, but they know who they are and good for them) may recall that I liked to point out a curious feature of our modern industrial-capitalist civilization.

On the one hand, the unprecedented increase in human productivity and the creation of prosperity starting with the Industrial Revolution was gained by intensively exploiting hydrocarbon-based energy. As scholars like Vaclav Smil or Joel Mokyr have pointed out, the economic and social transformation of modernity has at heart been an “energy revolution”; enhanced human prosperity is the by-product. This energy revolution, however, has had a very nasty side-effect, unforeseen in the formative stages of industrial production: the greenhouse effect, which is now rapidly warming the earth and imperilling the viability of the global ecosystem.

On the other hand, modern industrialised societies have ruptured the traditionally high fertility rates that human beings have practiced more or less from the moment we shifted into a sedentary agricultural mode of production. And this is what I want to focus on here.

It is estimated – and note these are very tentative reconstructions – that from a global population of maybe several million people at the end of the last Ice Age, ca. 12ka (i.e. thousand years ago), we increased in number to several hundred million by the year 0. By modern standards, that ain’t much. But compared to population growth over the preceding two hundred thousand years of our species existence, it was unprecedented. The reason that we became so much more fertile in our post-agricultural civilization was not, as one might expect, better food supply – skeletal analysis of early farmers versus hunter gatherers has shown poorer nutrition, poorer health, shorter statures, and shorter lives. Nor was it a more reliable food supply, since food supply in sedentarised communities was often less reliable. Indeed, there has been a growing consensus for quite some time now that the move into sedentarised agriculture, far from being a moment of great civilizational advance for humankind, represented instead a kind of social trauma that left most people in rather poorer state than they were before. Jared Diamond, for example, has called the transition to farming “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race,” which, considering the competition, is no mean title to confer. And the eminent scholar James Scott has made much the same point.

Instead, higher fertility was suitable to the new economic reality of agricultural production, and was then further enhanced by the social-cultural systems these spawned. When God commanded “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it,” he was talking to these new day-sixers, farmers and pastoralists; the hunter gatherers were still scrabbling around in day five. More children meant more labour, which meant more production: family assets could be grown in the womb so they could be sent to work in the fields. Simplifying obvs, but it’ll do.

Now, our normal perspective for thinking about population growth is concentrated on just the last century, with everything before then belonging to the period of technological primitivism, aka “the olden days.”

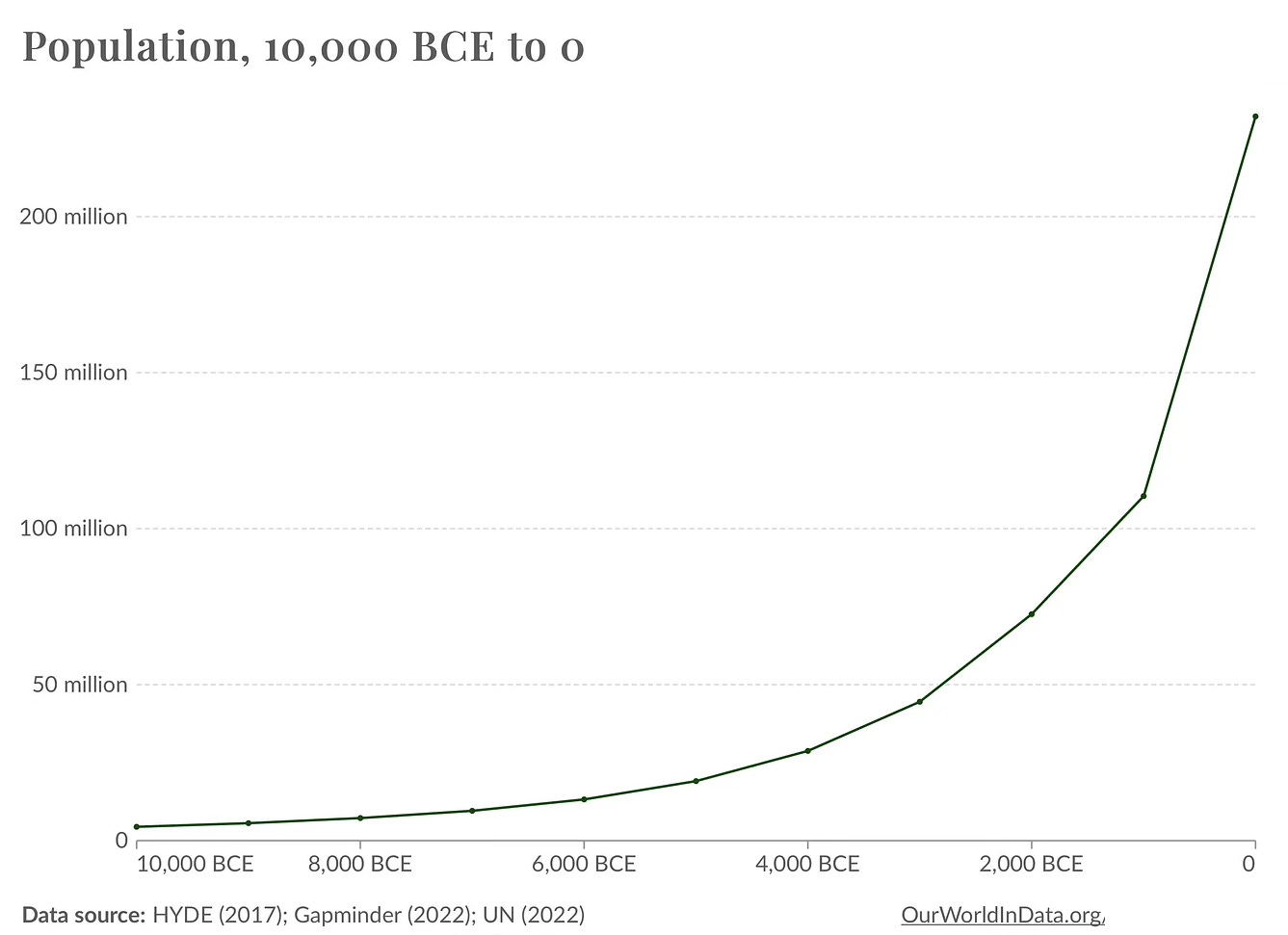

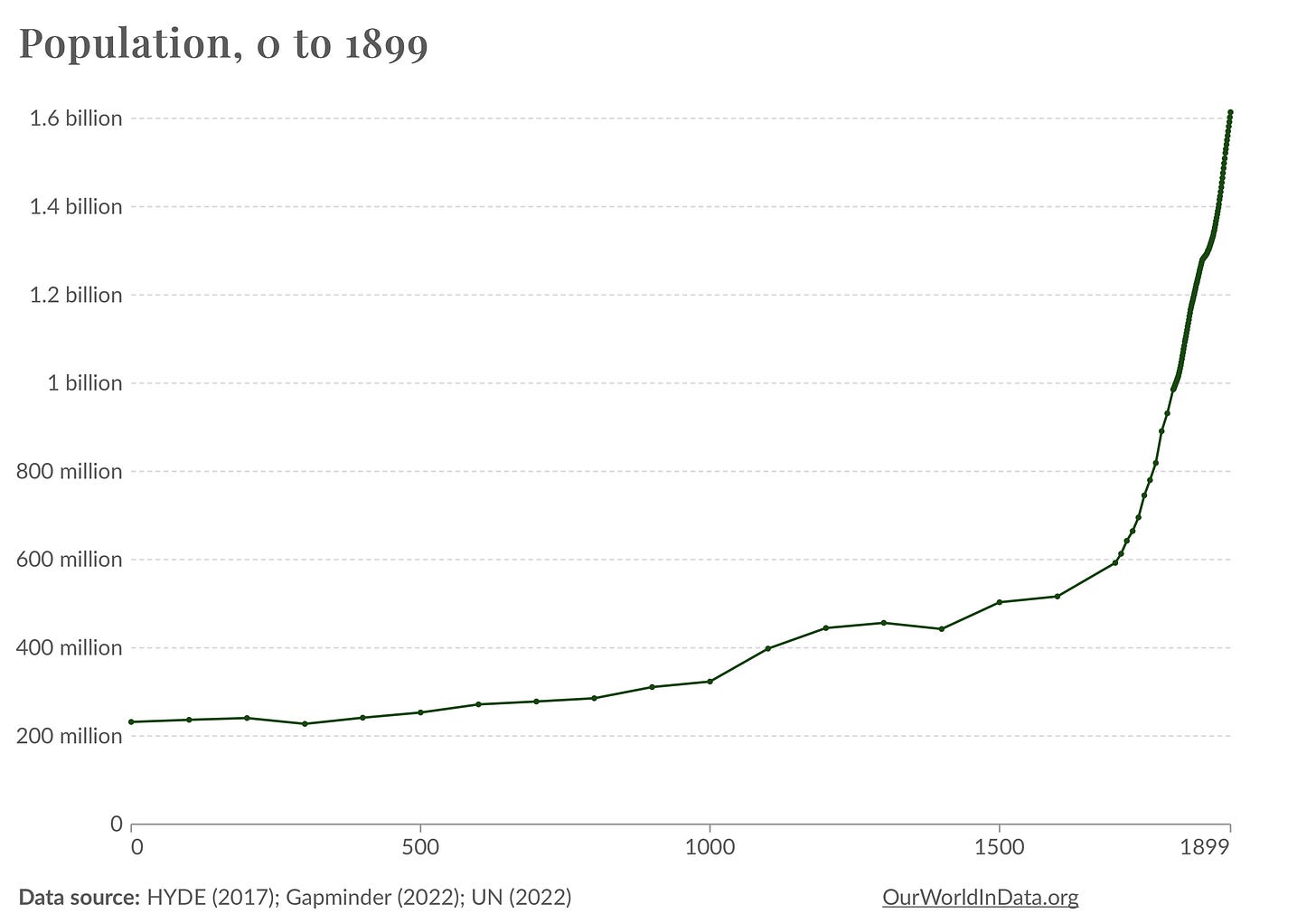

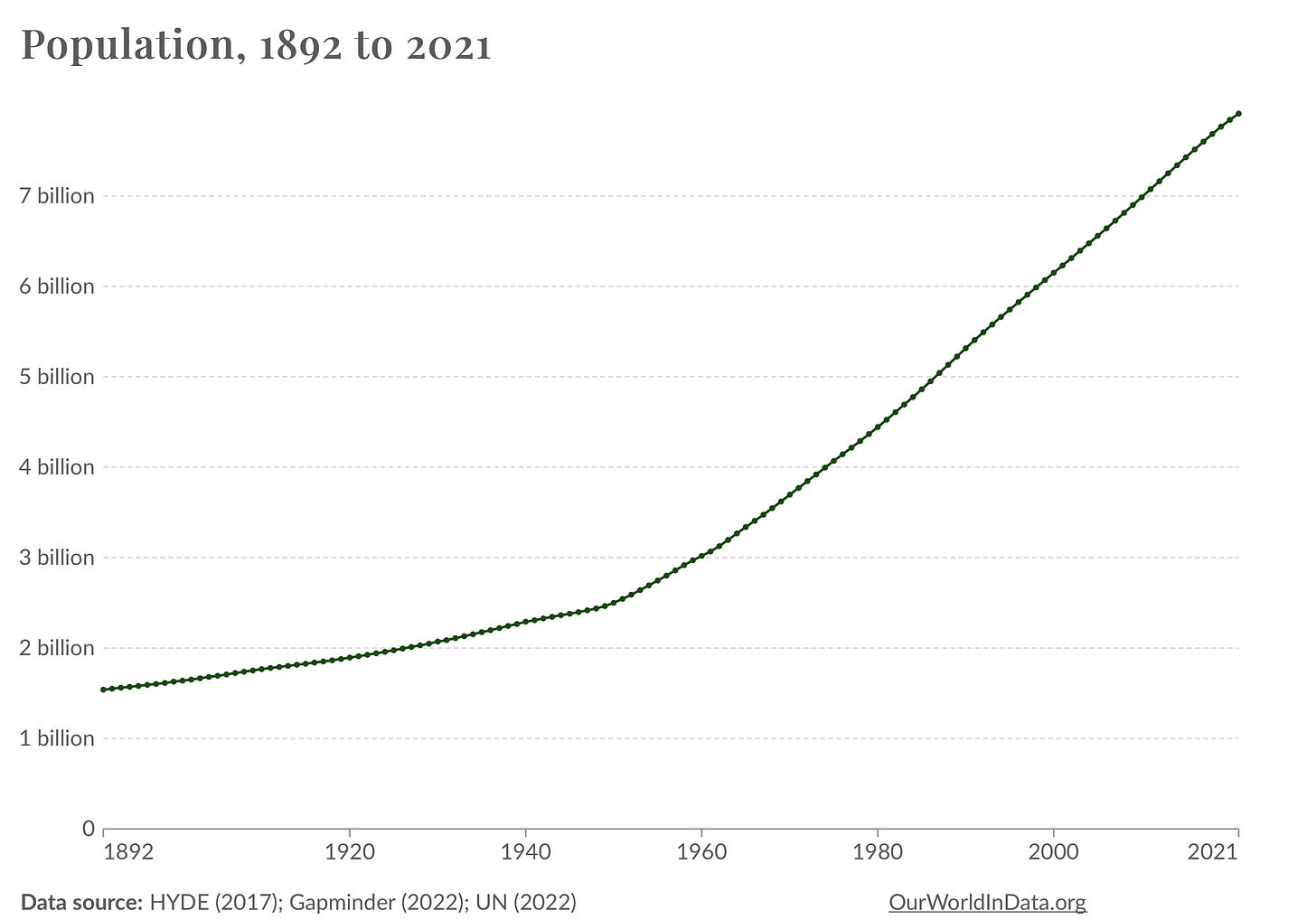

But that is wrong. It is much more valuable, analytically, to use the “dawn of civilization” as our marker, which, when divided into specific time periods (10,000 BCE to 0; 0 to 1900; and 1900 to present) reveals a recurring exponential growth curve, as you can see when we break it down into these logarithmic components: the pattern of the first 10 thousand years is then replicated over the next 1000 years (okay, fine, 2000 years, but the logarithmic progression still attains), and finally the last 100 years or so:

So look, I took like one demography class in college, and it was in French, and I skipped a bunch of lectures, so I am not saying I have any idea what I am talking about.

But if you look at these graphs what you see is actually a decline in the growth rate pattern over the last century: the predicted exponential take-off in the last decades has been comparatively muted compared to our previous experience. Which is just a roundabout way of saying that the rate of human population growth is slowing, and not just in developed countries, but globally.

Of course, the impact of innovation on population growth over the last hundred years has been phenomenal, and in sheer number terms overwhelms past figures. At a global level, infant mortality rates have plunged from over 50% prior to the modern era to less than 5% today, increasing overall population size due to enhanced longevity starting at the end of the 19th century. That created an incredible boost to available human resources, but also wrought all kinds of havoc on our human social systems (e.g. Germany’s population almost doubled between 1840 and 1914; Lebensraum, anyone?). But the big picture here is not that 100 years of unprecedented population growth is now projected to decline. It is that 10,000 years of an established, stable pattern of human fertility now appears to be coming to an end.

Do you like symmetries? I like symmetries, so here’s one. The last ten thousand years witnessed a stable climate and a stable pattern of population increase; now, we are seeing a rapid destabilization of both. And that’s not “rapid” in the sense of geological time, or even epochal time. If you, dear reader, are under 40, first, jealous, and second, we’re talking shit that is going down in your lifetime. And if you have kids, well, they are going to see some things.

This is not mere coincidence – they are causally linked. Yes, yes, I know, correlation is not causation, but in this case, bear with me. Because it was the stabilization of temperatures around 12 thousand years ago that gave rise to the stable pattern of human population growth which followed from the economic logic of sedentary civilization (note that I am boldly presenting as fact what are, in fact, generally-agreed theories so if you trot this shit out at cocktail parties, add in the usual provisos, “according to some shit I read once on some random Substack,” etc…). That civilizational process produced, in turn, the (eventual) amalgamation of innovation that produced the Industrial Revolution and, with it, the critical breakthrough moment for overall human prosperity.

But that human prosperity has been purchased – unwittingly at first, cynically now – at the expense of the very climate stability which provoked it in the first place. Which makes it look like a classic Faustian bargain: the achievement of a sedentary human civilization is a form of prosperity that undermines the very conditions that gave rise to sedentary human civilization in the first place.

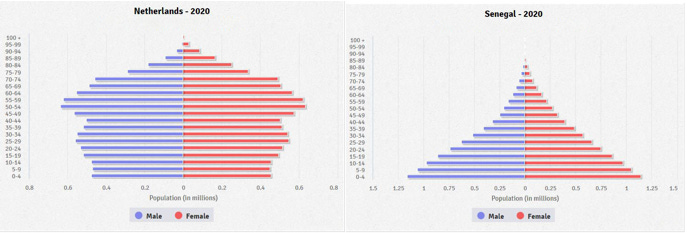

However, it turns out that, at the same time, it also put an end to the pattern of exponential population growth. Why? Because this prosperity, more precisely late-stage capitalist prosperity, is a fertility killer. And, to be clear, you don’t have to have a late-stage capitalist economy to suffer the fertility effects of late-stage capitalist prosperity (I’ll explore that curiosity in a subsequent post). As I noted in my earlier post, this is formally termed the “demographic transition,” which describes the correlation between the rising levels of the modern form of human prosperity and (rapidly) declining fertility. Another graph, anyone? Oh look, I have one here – population pyramids of The Netherlands (median age > 42) and Senegal (median age < 20):

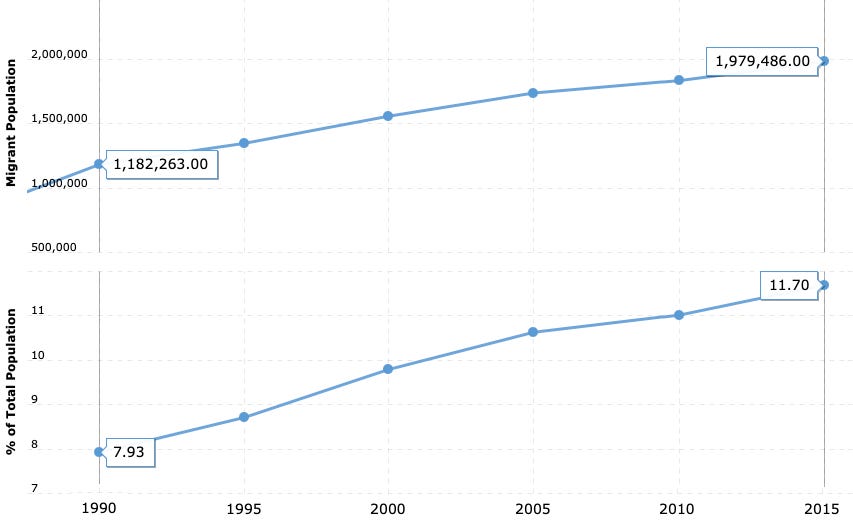

This is what a fertility rate of 1,62 (the Dutch) compared to one of 4,3 (Senegalese) looks like, and that’s after only about 1,5 generations (each generation calculated at roughly 35 years). And the situation would be even worse for the Dutch if they hadn’t brought in significant numbers of immigrants over the last 30 years. Oh yes, that’s another graph:

The Dutch population overall, and its younger component in particular, is being largely propped up by an influx of immigrants as the share of the native born declines. Given the low fertility rate, this will only intensify and goes to the point in my earlier post that the Dutch are trapped between a rock and a hard place reality, namely that they desperately need the immigrants that they (or at least a sizeable number of them) do not want. You can see that in the space of one generation (1990-2015), the share of the overall population made up by immigrants has increased by about 50%. That’s a formidable rate of change, even for the normally stolid Dutch, so little wonder Geert is out there making hay!

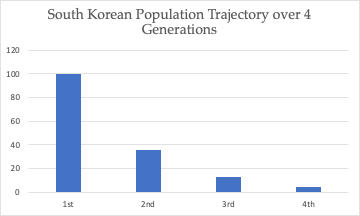

This is not, as I say, just a Dutch problem. This is happening everywhere around the globe. And nowhere with more intensity than the developed Asian economies. I mentioned in my previous post that the true standout for population collapse is South Korea, which already has an inverted pyramid, and will soon – like within a few decades soon – be an ungainly top heavy edifice of the superannuated supported by the thinnest of youthful demographic foundations. At the current fertility rate (an astonishingly low 0,72/woman and still declining), the pace of population loss is breathtaking:

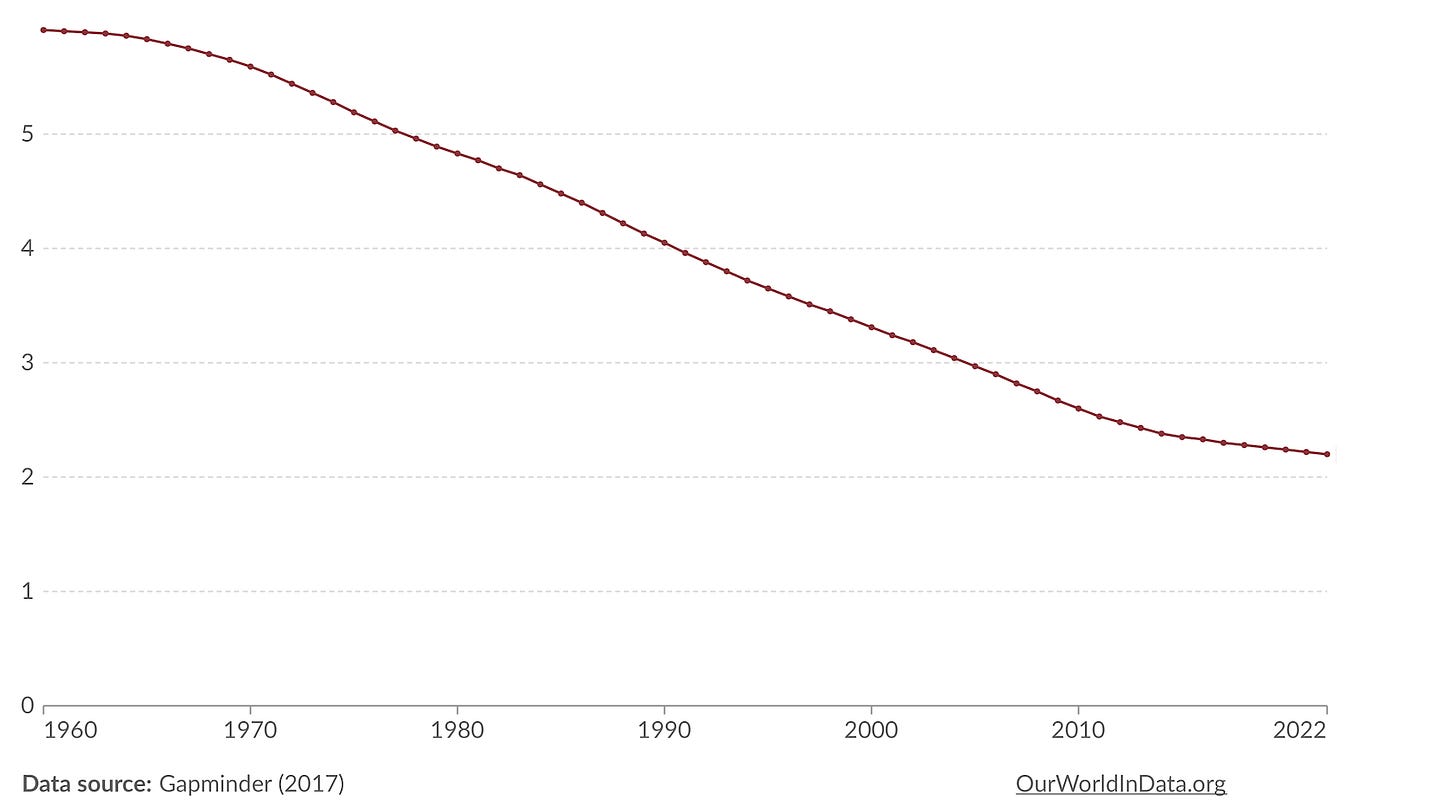

What this means is that 100 South Koreans today will have less than thirteen grandchildren (~ 70 years from now) and less than FIVE great-grandchildren (~100 years from now)! The South Korean example is an exceptional and vivid example of this global phenomenon, which shows that, if existing trends continue, once the maximum global human population is reached (projected within the next decades at about 10,5 billion) there will be, given the elasticity of population change, a significant and rapid decline. For example, guess the fertility rate of India, which last year became the world’s most populous country (just under 1,5 billion). I bet your instinct tells you it has a very high birth rate. Nuh-uh. The prosperity gains that have been notched up in that country and the corresponding drop in fertility over the last 50 years are exemplary of the demographic transition. In 1970, India’s fertility rate was estimated at about 5,6; by 1990 it had fallen to 4; in 2022 it was 2,2 which is about the replacement rate, and it is just a question of a year or two before it falls below that threshold.

And already in certain parts of the country, the fertility rate is well below the national average, on par with that of developed Western nations, and not just where you might expect, e.g. the wealthier enclaves. In the state of Sikkim, the rate has plunged to 1,1!

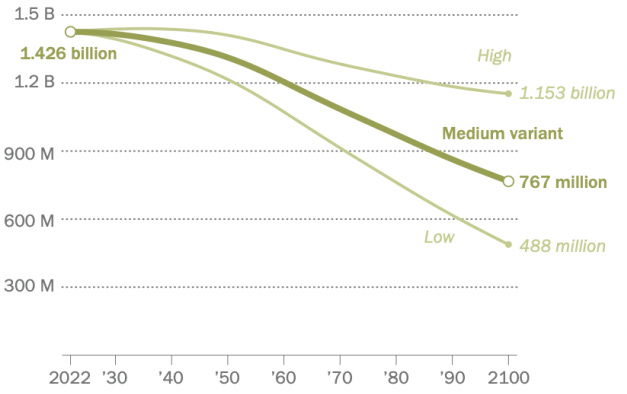

In short, much of the population growth that took place in the first century and half after we entered the industrial phase of human civilization will be lost over this century. Global population projections through to 2100 from the UN and similar organizations need to be taken with a great deal of circumspection because the rate and pace of demographic decline is happening far faster than earlier models had anticipated. Look at China as an example. It only eliminated its one-child policy in 2015 (its fertility rate is around 1,7) and now is projecting a very significant population decline over the course of the century that was essentially unforeseen even just a decade or so ago:

The “medium” variant in this graph, which shows about a 50% population loss over the century, is probably rather optimistic; if China’s fertility profile inclines even partially to that of its neighbours (Japan or South Korea) then the low projection is much more realistic.

There are significant near-term consequences for those who will live out their lives in this first phase of population retreat, which makes sense if you think about it. The rapid upward increase in population (i.e. in sheer number terms) after 1900 meant that we enjoyed a period of prosperity where lots of productive young people overwhelmed the effect of an aging population created by new technologies that greatly increased longevity. Unwinding that trend will produce the reverse: lots of old people who will increasingly outnumber the dwindling number of younger, more productive folks.

And who is going to be in the middle of that maelstrom? Our children, i.e. anyone born after 2000, and especially those born after 2020. They will be the first to face head-on the twin consequences of our civilizational experiment: a rapidly warming earth AND a rapidly aging population, of which they will be the pioneering generation.

I’ll consider what that might look like in part 2.

THANKS for reading – throw a fellow a like wontcha? Apologies (again) to my Dutch reader (not a typo), and please feel free to comment or to share this post with anyone who might be interested. Tot ziens!