A Lonelier Planet (Part 2)

What are the main drivers that explain why we're having fewer kids? Many point to our modern economic prosperity and social progress. But there's another, darker explanation.

This series of posts explores the convergence of two trends that have already begun to happen and will have an increasing effect on people’s lives going forward. Someone born this year will spend their senescence in the 22nd century, by which point the circumstances of their lives will be greatly affected by two deep-seated, unstoppable trends: a planet that is both warmer and lonelier. What will this look like?

You can find the other posts in this series here: Part 1 & Part 3

Back in the 1970s, or as my students think of it that period that falls sometime after cavemen and before TikTok, there was much handwringing about two unrelated, long-term crises. Amidst all the gloom of Watergate, the Vietnam War, oil shocks, inflation, bell-bottoms, disco, and the inexplicable surge of orange and brown as fashionable colours (I mean, really?), there were two long-term trends that attracted a good deal of attention.

The first was the idea of a “population bomb,” named after a book of that title written by the Stanford professor and lepidopterist (go on, look it up) Paul Ehrlich was published in 1968. As Ehrlich surveyed the future of the species, it looked to him pretty grim. He foresaw an unprecedented Malthusian crisis unfolding across the globe, an untrammelled expansion of the human population that would lead to the severe depletion of the earth’s resources. At the same time, a couple of European folks were also thinking about how shitty the future was going to be, extrapolating from the prevailing trends of population increase and economic growth to conclude that the runway for continued human prosperity was rapidly growing shorter. They institutionalized their concerns in a thing called the Club of Rome and published a famous report in 1972 entitled the Limits to Growth. Underlying both of these approaches was basically the same idea: runaway population growth would lead to an earth inhabited by, say, a 100 billion of us, scrabbling away to survive through the short-sighted depletion of all available resources, which would lead, ultimately, to a collapse into some kind of Hobbesian hellscape.

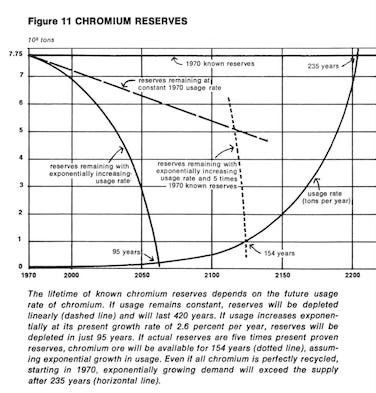

The Club of Rome, for instance, singled out the metal Chromium as a proxy for our impending catastrophic descent into resource depletion. I am not sure why they picked Chromium to be the poster child for the fate of humanity, but why not – it is, coincidentally, thanks to a school project, my kid’s favourite element, and the subject of one of my father’s least cited papers (“Ultrasonic attenuation near the spin-flip temperature in chromium” – not throwing shade there, because that paper still has more citations than any of my work). Using various projections they produced one of the ugliest graphs you’ve ever seen to show we’re basically fucked Chromium-wise, and, by extension civilization-wise (Have you heard about that thing with Chromium? Better build your survival bunker, jus’ sayin’). I especially like the insertion of the dashed falling-of-the-cliff line in the middle of the graph that just floats there as some kind of harbinger of doom.

The message was clear: too many of us are consuming too much, too quickly so we need to figure out a way to stop before the system collapses. Indeed, the Club of Rome folks warned that by the 22nd century we’d see a period of rapid, chaotic population decline, triggered by the sudden unavailability of food and other critical resources (I mean, we’ll be fresh out of Chromium by 2150). Like Ehrlich, they also saw population explosion as the primary worry, and thus argued for the immediate implementation of aggressive family planning measures to manage human reproduction. And I’ll simply note, by way of pointing to the larger effect of these concerns, that China’s One Child Policy was introduced in … 1979.

The second major source of handwringing in the 1970s, as people were grooving to the Bee Gees, wearing orange, and popping ‘ludes, was: the coming of the next Ice Age. This particular concern has had a long shelf life in large measure because (what we now know was) fossil-fuel industry-sponsored climate-change denialism liked to point to studies from the 1970s predicting a long-term cooling trend to undermine the gathering evidence of global warming. Without bothering going into all the details of why some scientists thought the earth was moving towards a cooler average temperature, the basic fact is that the earth is in an inter-glacial period of the Quaternary glaciation and so we’re due for a reversion back to an ice age. That is, until we decided to release a fuckton of carbon into our atmosphere and changed the underlying climate dynamics of our planet. But back in the 1970s, all that was not so clear. I mean look, you try to figure out what the hell is going on when the background soundtrack is Staying Alive.

So, to summarize, in the 1970s we had: bad politics, bad economics, bad fashion, AND doom and gloom everywhere about runaway populations and an imminent return to the Ice Age. The music, however, was – admit it – a guilty pleasure. And if you have staying alive running through your head right now, you know it's all right, it's okay and you’ll live to see another day, which was the kind of message people needed in the 1970s because see above.

So. Let’s take a moment to reflect on where this stands on the spectrum of error. We have at one end just your standard issue being wrong about things (e.g. me making up stuff in the classroom with a say 40% accuracy rate), and then we have varying intensities of wrongability scaling up, and at the far end of that spectrum we have a special kind of extreme wrongness, the Ehrlich-population-bomb/ice-age-is-imminent kind of completely, absolutely, totally wrong in every way kind of wrong.

Because as we consider the future today, armed with admittedly better science, more precise data, and a much more nuanced approach to building out models that extrapolate from existing trends and observations, we see exactly the reverse of what kept people awake in the 1970s. Not an exploding human super-population leading to Malthusian misery, nor a plunge back into a world of ice, but instead a much lonelier and much hotter planet. I mean, it is still grim. Very grim in fact, just a different kind of grim.

So what led to these absurdly erroneous predictions? I’ll leave the climate stuff aside, and instead focus on the issue of population. In effect, the pop-bomb folks fundamentally misinterpreted the trends that had been developing throughout the 20th century. They falsely assumed that the pattern of exponential population growth would only falter (absent urgent social policy measures) when the physical limit of how many people the earth could sustain was approached. This is the classic Malthusian scenario. And it was not just Malthusian in a strictly numerical sense of geometric growth curves. It was also culturally Malthusian. This is because Malthus’ famous discussion of population catastrophes (i.e. arithmetic increase in food supply leads to geometric increase in reproduction, which then exhausts available food supplies and produces famine, misery, and death) was based largely on his contempt for the Poors, who (in his view), not knowing any better were just ignorant baby-factories doomed to perpetuating their own poverty unless they were held in check by a healthy dose of disapproving and moralising Anglican upper-class attitudes that could lift them from their morally-depraved existence. When the Irish famine happened, starting in the 1840s, this kind of Malthusian moralising was so prevalent that the attitude of the (Anglican) British government, whose estimation of the (Catholic) Irish fell somewhere between bole weevils and marsh gas, led it to restrict emergency food relief, basically, to teach them a lesson, or as they might have said, for their own good. The concerns surrounding overpopulation in the 1960s had a similar kind of cultural prejudice built into them. Once again, all those depraved poors were wantonly fornicating like out-of-control sex-crazed lemmings, but this time in places like Asia or Africa, and unless the wealthy, educated parts of the planet did something about it, we were all doomed.

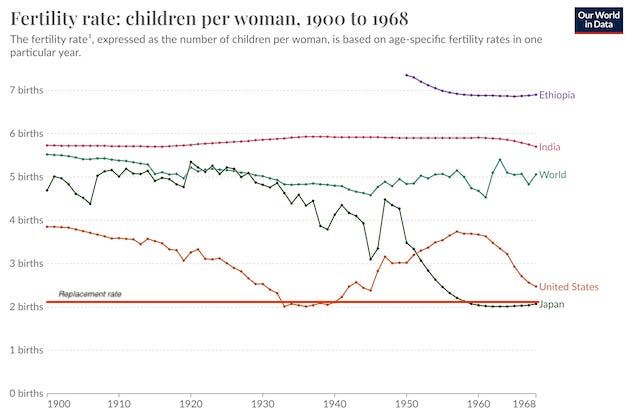

So consider the perspective from 1968, the year of Ehrlich’s book. First, across the globe the total fertility rate (TFR) was high. While the TFR of most industrialized countries was declining after the postwar baby boom years, those of developing (i.e. non-white) countries remained very high. And combined with much lower mortality rates thanks to improved disease control, the overall (again, largely non-white) population of the earth was increasing at a torrid pace. And it is also important to bear in mind that for many of those developing countries the true state of affairs regarding populations and TFR had only recently come into view as a result of better statistical measures.

So the (mostly white) Ehrlich types, as they read the numbers through their colonialist-tinged glasses, saw an out of control population pattern. While increased prosperity (e.g. US, Japan) led the TFR to regress to the replacement rate, the bulk of the world’s fertile women, since they were living outside of industrialised economies, would remain hyper-charged breeding machines for the foreseeable future. And in a very narrow sense, the pop-bombers got it right. In Ehrlich’s lifetime (he was born in 1932 and is still alive), the earth’s population has climbed from roughly 2 billion in 1930 to over 8 billion today (i.e. 2^3). But they sorely underestimated, or really just overlooked, the highly elastic nature of population dynamics.

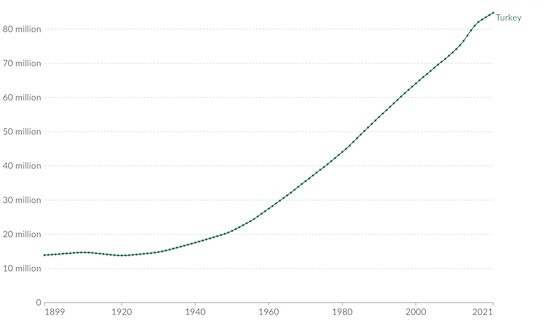

The error was linked to the prevailing view of the demographic transition, or DT (outlined in my previous post). Under the DT model as it was understood at the time, increasing wealth would eventually reduce a country’s TFR to about the replacement level (2,1 children per female). So the idea was that a country would see very significant population increase during the first period of its transition, followed by stabilisation once a certain level of development (typically measured in terms of per-capita GDP) was attained. So here, for example, is Turkey (ve üç Türk okuyucuma merhaba!), a country that is currently entering the low birth rate stage of the demographic transition:

From the pop-bombers perspective, they would see in this graph a perfectly reasonable number of Turks in 1900 (13M) explode into an entirely unmanageable number of Turks 100+ years later, which would then stabilize at this new, unreasonable level. And since the only thing that brings down birthrate is development, all those modern-day Turks would be consuming resources at a far, far higher rate than their poor counterparts in 1900. Thus, a new equilibrium would only be reached after a sixfold increase in population, combined with a tenfold (or thereabouts) increase in resource consumption per person. Apply that logic at global scale, and you can see why they were catastrophists.

BUT, as we now know, the DT does not produce a fertility rate that stabilizes at replacement. In fact it falls significantly below replacement rate. And because of the geometric nature of population change, even a relatively slight drop below replacement rate will have a significant effect on overall population size.

This phenomenon is captured by something called the Second Demographic Transition (SDT), which describes why birth rates do not stabilize at replacement levels, but instead cruise past it like the cool kids on their way to a Taylor Swift concert, and plunge to the depressed levels that we see in all developed countries.

Now, you might ask why we need a second demographic transition to explain … the demographic transition. My guess is that the SDT is mostly just flummoxed researchers trying to figure out why their original models were wrong. But there is one way that the SDT is helpful, which is that it allows us to separate a purely economic case for declining birth rates from what we might term a socio-cultural one.

There are many theories about what, exactly, triggers the shift into the phase of rapidly falling birth rates. Generally, development is seen as critical since it changes the underlying economic argument about having kids. When you are very, very poor, children represent assets. I will note as an aside here, that as Marshall Sahlins put it “the world’s most primitive people have few possessions, but they are not poor,” which explains why birth rates of surviving hunter-gatherer peoples remain low. But for the (usually agriculturalist or pastoralist) very poor, children can be put to work for you, tilling the fields, tending the cattle, hauling the water, or making your next carpet. As societies become wealthier, however, the economic logic of childbearing changes. At a certain point – and it is remarkably consistent across radically different societies – the underlying accounting changes. Instead of assets, children shift suddenly into liabilities - or, we might say to make it sound a little nicer, they become (from the perspective of the parents) non-productive assets. Since we seek as a matter of self-interest to maximize assets and minimize liabilities, average family sizes plunge once that threshold is breached. Indeed, the speed of this decline has been breathtaking, starting during the second half of the 20th century:

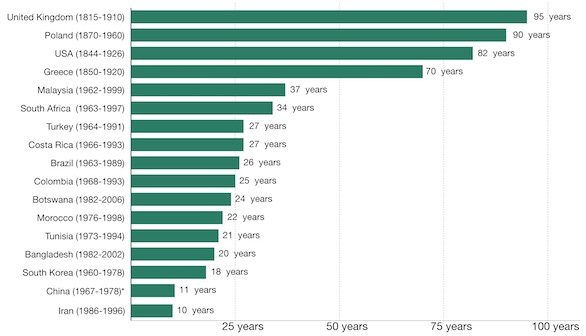

There’s lots of counterintuitive stuff in this graph. For example, the plunge in China’s birth rate occurred before the one-child policy, which was, in retrospect, an ideologically-driven, poorly-conceived, and totally unnecessary measure, since China’s economic development – even before the Xiaoping era – had already triggered the shift. And note Iran, people: the rapid plunge in its birth rate took place after the Islamic revolution, which in many respects was highly regressive with respect to women’s rights (but not, notably, in terms of educational opportunity). On the other hand, in Québec (where I’m from), the birth rate of the French-speaking part of the population collapsed rapidly – in less than half a generation (<20 years) – after the Revolution Tranquille of the 1960s put an end to the monopoly on social mores exercised by the Catholic Church. More religion? Fewer births. Less religion? Fewer births. Clearly, such social institutions are not the culprit.

The real answer, then, is simply the impact of industrial/economic development. This explains why for those countries where the pattern of economic development unfolded over a long period of time (Europe, US) the transition took longer. For more recently industrializing countries, which have been able simply to import a model of development worked out over a century or so in the West, the effect is hyper-accelerated. And perhaps most surprising is that the relationship between wealth creation from economic development and TFR is much, much, much lower than you would think: GDP per capita in Brazil in 1989 was roughly $2800; Turkey in 1991, $2750; Morocco in 1998, $1500; and Bangladesh in 2002, a mere $408! (Those are controlled current dollar figures.) And those numbers are pretty crude. If we factor in the Gini coefficient – which I am not going to do because that would require effort, and this is a low-effort substack – the result is that for most people the level of economic development was much lower than these top-line figures would indicate, because there is a strong correlation between economies in their developing stage and very lopsided income/wealth distribution.

Anyway, the point is that not very much wealth has a very big impact on family size. This reinforces the point that the demographic transition is really part of the larger paradigm shift of industrialization.

Another factor that has been widely cited as linked to the DT/SDT is female literacy rates, or, extrapolating, female educational attainment. This explains, perhaps, why Iran’s birth rate fell as quickly as it did. Despite various efforts of the Ayatollahs to slap hijabs on all their lady folk and push them back into the Old Testament, the trend towards higher rates of female educational achievement established prior to the revolution continued; Iranian women have outnumbered men in post-secondary education, for instance, for decades, even if the subsequent economic opportunities for those educated women remain restricted.

There is a strong correlation between female levels of education and the average age of first birth, which is another major factor in lowering the TFR. A recent gathering of demography wonks here in Spain led to plenty of handwringing and alarmed headlines about the fact that the average age at which a Spanish woman has her first child is 32! Since female fertility starts declining from the age of 30, and diminishes rapidly after 35, this means that absent immigration, the Spanish population is hurtling towards its gerontological future with ever greater momentum. And while at the vanguard among European nations (along with, of all places, Malta) Spain is simply indicative of a trend that has taken hold across the continent.

In 1980, the French historian Philippe Ariès argued that this development towards below-replacement birth rates was linked to an attitudinal shift, in which having children was no longer the primary focus of reproductive-aged couples. I mean no shit, but since I went to the effort of digging up his article (“Two Successive Motivations for the Declining Birth Rate in the West”), here’s a quote:

I feel that a profound, hidden, but intense relationship exists between the long-term pattern of the birth rate and attitudes toward the child. The decline in the birth rate that began at the end of the eighteenth century and continued until the 1930s was unleashed by an enormous sentimental and financial investment in the child. I see the current decrease in the birth rate as being, on the contrary, provoked by exactly the opposite attitude. The days of the child-king are over. The under-40 generation is leading us into a new epoch, one in which the child occupies a smaller place, to say the least.

There is no question that, for developed economies especially, the concept of the “couple as king” replacing the “child as king” model is operative for many. But this is not just a question of couples making a kid-free future full of nicer things, better vacations, and less hassle than would be the case with a house full of brats a priority. Something else going on: the impact of living in (or adjacent to) the wage-driven labour system created by capital-driven markets. And I think the impact of this system shows up in one very interesting metric.

Which is: in many countries, the observed fertility rate is below the desired fertility rate – i.e. couples are having fewer children than they would like. In both France and Spain, for instance, which have fertility rates of 1,78 and 1,29 respectively, the desired fertility rate is at or slightly above replacement level (2,1), which is exactly what the DT predicted would be restabilization point after the transition stage. So the point is that falling birth rates via deferring the age of first birth, and/or having fewer or no children overall must be related to external circumstances that go beyond simply the “couple as king” model.

And I think we all know what those external circumstances are: economic security. This can be seen by the simple fact that the natalist policies that most governments have resorted to simply involve giving cash to new mothers; that is, a straightforward effort (i.e. bribe) to offset the financial consequences of childbearing. Or as Richard Thaler might say, a nudge – although not a very subtle one, more like a shove maybe.

In South Korea, for instance, to solve the depopulation crisis, the government has nakedly transactionalised the issue by paying women ever-increasing amounts to have children:

Since 2022, mothers have received cash payments of 2 million won ($1,510) upon the birth of a child…. Families receive 700,000 won ($528) in cash per month for infants up to the age of one and 350,000 won ($264) per month for infants under two, with the payments set to rise to 1 million won ($755) and 500,000 won ($377), respectively, in 2024. A further 200,000 won ($151) per month is provided for children up until elementary school age, with additional payments available for low-income households and single parents.

Other benefits include medical costs for pregnant women, infertility treatment, babysitting services and even dating expenses. (My italics)

When the government is picking up the tab for your Tinder subscription, you know things are bad.

But – shock – these tactics don’t work. No person is thinking, well I wasn’t going to have kids but OMG I can’t leave a few hundred bucks a month on the table, so turn down the lights and let’s pitch some woo. Well, maybe a few think that, but not enough to make any difference. Because actually to have an impact, the amounts that would have to be paid would be much more than any government, at the moment at least, could see its way to actually forking out – like thousands, not hundreds a month. And over a long time, too, not just the diaper years. And that doesn’t even touch on the larger questions of economic opportunity costs and, especially, affordable housing which in many places has become a touchstone of concern, if not outright grievance, dissuading couples from having kids earlier. Absurd housing markets (as I discussed here) are an unsung abortifacient of the 21st century. Yes, I just went there. Deal.

The question of economic insecurity for the potential parent is further compounded by the perceived level of investment needed to allow children to themselves become competitive in a tight labour environment. While it may seem that the higher one’s aspirations for one’s children, the higher the attendant costs (which in real dollar terms is undoubtedly true), I suspect that nonetheless the level of investment probably scales as a function of income, such that the “investment burden” remains largely the same. (I am literally making shit up now. You should probably stop reading.) I base this on the logic of Veblen, who pointed out that aspirational consumption exists on a relative, not absolute scale. You may not envy the billionaires their yachts (too far out of your league), but you might envy your neighbours their nice car. Since children exist inside an aspirational frame, I suspect this effect holds true for them as well. Thus, despite the common perception (cultural Malthusianism again) that the poors have lots of kids because they don’t give a shit, while the middle class dithers and frets while putting money away for future IVF treatments (cf. the opening of Idiocracy), the reality is that the investment costs of having children remain more or less stable as a function of total family resources, which explains why rich or poor, birth rates are in steep decline. Indeed, in developed countries the only folks who have consistently high birth rates are those of communities (like the Amish or Hassidim) who are self-consciously outside of, and even militantly reject, modernity – in other words who live lives beyond the logic of our industrial economic paradigm.

Thus, a system that encourages economic anxiety and promotes what some might call wage suppression, but what others might call labour cost optimisation, via the use of competitive (i.e. deregulated) labour markets and/or the discouragement of institutional mechanisms (i.e. unions, regulation) to establish higher levels of employment security is going to be a system that, as a side-effect of those labour cost and other market efficiencies, will inexorably push overall fecundity downwards. Increasing female labour participation rates reflect the need to offset diminished wage earning potential; family planning, later ages of first birth, and childlessness reflect less lifestyle, and more economic choices – thus the observed discrepancy between actual and desired fertility. And these are inevitable consequences of the higher structural costs of establishing family security.

This post is too long, so let me wrap up. It strikes me there are two stories lurking here. One is fundamentally a story of triumph: gender equality, female empowerment, educational advance, economic development, and the lifting of people out of endemic poverty. The other, however, is decidedly more bleak: economic uncertainty, competitive labour markets, high costs of living, and an inexorable concern over the future well-being of offspring who are born into this age of anxiety. It is a great irony that in this age of unparalleled plenty, it is clear that there are many who perceive themselves to be in a position too uncertain, too unsettled, too poor to be having the children they might otherwise want.

Of course, these observations, and the prognostications that follow from them, may prove to be as erroneous as those of the 1970s. But if the trends continue as they are now, then we need to brace for a world that is shaping up to be very, very different from the general expectations that have broadly framed our thinking looking forward. That’s next time.

Thanks for reading, and please throw me a like. Also, feel free to share this post with anyone you think might be interested, or simply don’t like very much.

Is anyone serious discussing a circular or steady-state economy to manage these things? Putting aside the political impossibilities of those things, surely won't our hand be forced at some point to consider them?