A Lonelier Planet (Part 3)

What Alexis de Tocqueville, Danish rap music, and Angela Merkel can tell us about how demographic change will affect our future politics.

This series of posts explores the convergence of two trends that have already begun to happen and will have an increasing effect on people’s lives going forward. Someone born this year will spend their senescence in the 22nd century, by which point the circumstances of their lives will be greatly affected by two deep-seated, unstoppable trends: a planet that is both warmer and lonelier. What will this look like?

You can find the earlier posts in this series here: Part 1 & Part 2

The French thinker Alexis de Tocqueville wrote his celebrated (if way too long and painfully detailed) text Democracy in America (1840) to explain to his European readers what they needed to know about what he saw as the inevitable arrival of a frightening new political reality in the near future: democracy! For many among the European bourgeoisie and (especially) aristocracy, the idea that the common hoi polloi and unwashed riffraff could somehow acquire political rights and take a degree of control over their own affairs was, as the chaotic violence of the French Revolution had made abundantly clear, a frightful and terrifying prospect that should, on principle, be opposed. Indeed, the whole point of the post-Napoleonic order that had been established after the Congress of Vienna (1815) was (1) to make sure the French knew their place and stayed there, and (2) to prevent the dangerous and misguided progressivism of republican ideas promoted by the revolutionaries from ever gaining a foothold again.

It is true that the various blue bloods who assembled in Vienna recognized (rather begrudgingly) that some of the worst excesses, irrationalities, and abuses of ancien regime Europe which French occupation had done away with (e.g. certain clerical privileges, outdated taxation systems, the Holy Roman Empire, etc…) should remain permanently curtailed. But one thing they could pretty much all agree on was that democratic republicanism was a bad, terrible, awful idea and, should it ever resurface, must be stamped out, as it would only result in disorder, chaos, and the wrong people in charge. The deeply conservative Austrian diplomat Klemens Von Metternich, who was the chief architect of the Congress System, would later write that the restoration of a world which carefully concentrated privileges and power in the hands of a few was actually for the good of the many, since what would these people do with political rights they neither wanted, nor knew how to exercise responsibly. Better to leave it to an aristocratic class whose breeding ensured responsible government.

Hence: de Tocqueville’s text, which served to make three points. First, that ordinary people were not idiots and they could understand that they were not, in fact, like children who needed aristocrats in loco parentis to send them to their room so they could learn to behave properly. Second, that eventually this self-awareness would lead to some kind of clamour for a system based on democratic political rights. And third, that, yes, the French had indeed fucked it up after 1789, but hey - those pesky Americans seem to be doing democracy pretty well (slavery notwithstanding, as he notes), so let’s take a look at how they are getting it right, so that when it happens here, at least we’ll have a clue.

His call for an embrace of this new reality is summed up in a famous line: “a new political science,” he proclaimed (thereby summoning that term into existence) “is needed for a world altogether new.”

I have lately been reminded of de Tocqueville’s work in the context of my current preoccupation with our “lonelier (and hotter) planet” that will unfold over the next several generations. As patient readers of this ‘stack will know, I have been considering how the world as a whole, and developed countries in particular, are on the cusp of a major demographic shift, one that will occur in the context of climate change, which, sadly, will exacerbate the perturbations triggered by this shift. The obvious, inescapable, and ineluctable reality that will play out over the next two generations is that populations in developed countries will, absent remedial steps, not just decline, but indeed plunge, as total fertility rates fall ever further below replacement rate.

As I noted in my last post, the causes for this so-called “second demographic transition” are complex and can be interpreted in curiously opposite ways. One – as a triumph of female self-actualisation, in which literate, educated, professional, and ambitious women claim their rightful space which, for ten millennia, has been denied them. Otherwise – a consequence of the relentless grind of the wage-earning economy in capitalist-inflected market systems, which makes the cost of reproduction increasingly burdensome, leading many to delay or avoid altogether having children, thereby lowering overall fertility.

Glass half full or half empty perhaps? Either way, the upshot is the same. Falling birthrates, inverted population pyramids, and a near-term future that looks increasingly precarious as social obligations made under one demographic paradigm will have to be reckoned with under a new one.

Bar some miraculous reversal of the existing fertility trends over the next fifty years, what this means is that developed countries will face an ageing and dwindling population, thus presenting their politics with a stark choice. Either accept the population retreat and adjust as best you can through some kind of managed decline (the Japan model), or else import people from abroad to make up for the shortfall in the native born, aka immigration.

Just as de Tocqueville foresaw a democratic trend that would shape the future of European nations in the nineteenth century, so too can we foresee what I might call a “diversity” trend coming in the twenty-first. And a key feature of the de Tocquevillian text – that is, the way he elaborated its core ideas, the age in which he wrote it, and the folks for whom it was written – was that it was intended, if not entirely to reassure, then at least to assuage a sceptical power-holding elite that democracy, distasteful as they may think it to be, was not in fact the end of the world – in fact, when implemented well, it could do quite a lot of good for a people. In other words, his new political science was in large measure necessitated by the widespread hostility towards a change that he (correctly) predicted was inevitable and could, given the right knowledge and attitude, be made workable.

We are already seeing, and will, I suspect, continue to see with ever growing force, a similar sort of hostility to the kinds of changes that the second demographic transition will necessarily engender across many developed, post-industrial economies around the globe, namely rapidly changing ethnic compositions of national populations as immigrants flow in to make up the shortfall in native-born populations.

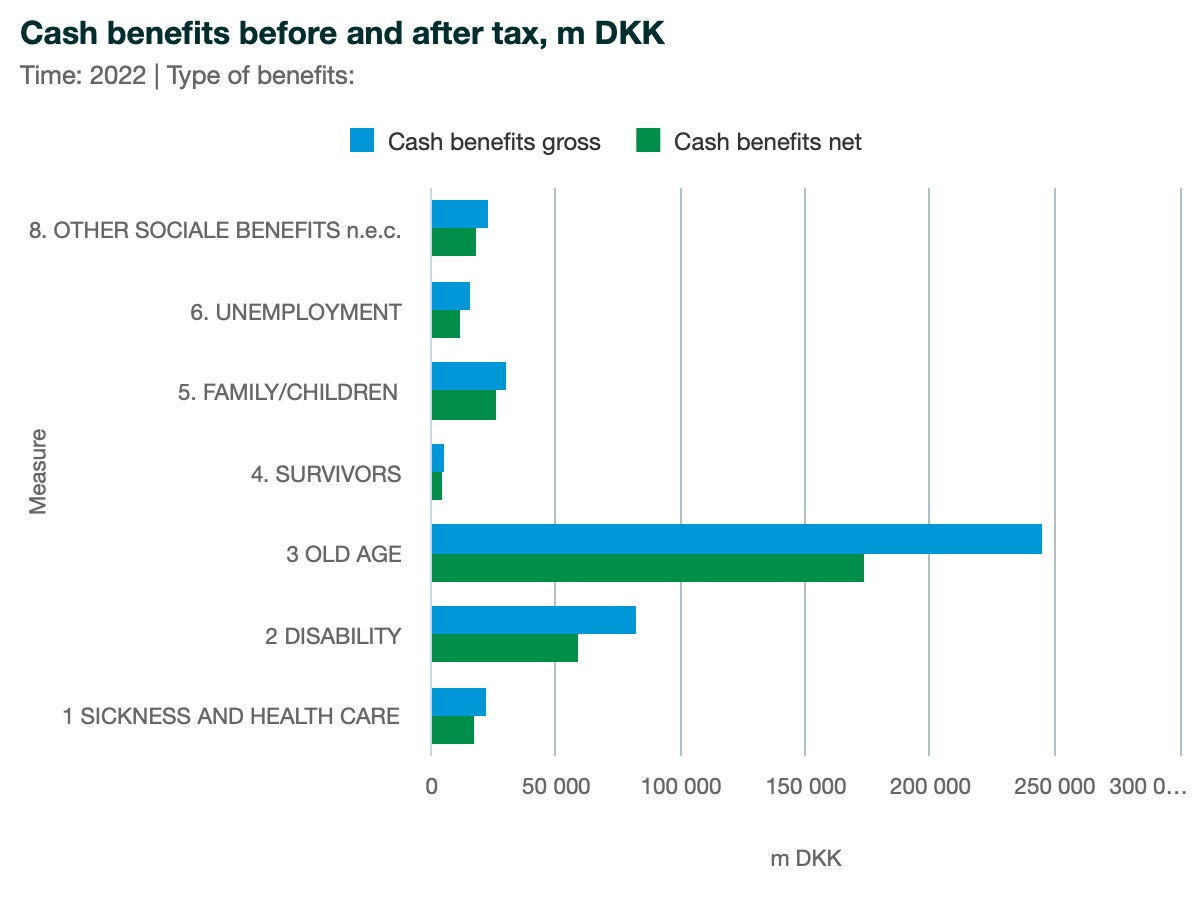

Let’s take Denmark as an example: small, largely white, hopelessly Lutheran in its cultural outlook, and regularly singled out for its fiscal responsibility and good government (that’s Lutheranism for you). It is one of the few countries, for instance, that runs a government budget surplus; its current debt load is at a 40 year low. Now if we dig into Danish government accounts (which I have done so you don’t have to), what do we find as the single biggest expenditure? If you guessed old-age related expenses, you get a gold star! ⭐ Of the direct cash benefits paid by the state, the overwhelming majority of it goes to old-age pensions (although it is true that some of that is subsequently clawed back in taxes):

On top of that, there are the indirect benefits, by far and away the most important of which is government health care expenditure. Since healthcare is consumed disproportionately by the elderly, what this means is that a majority of the state budget goes to supporting old Danes. And nothing wrong with that. Who doesn’t love an Old Dane. But the point is that Denmark is exemplary of the fact that the structure of government budgets in developed countries skews heavily to providing services and support, both direct and indirect, to older people. And as an already fairly old and, despite my best efforts to stop it, a constantly-getting-older person, I personally have no problem with those budgetary priorities.

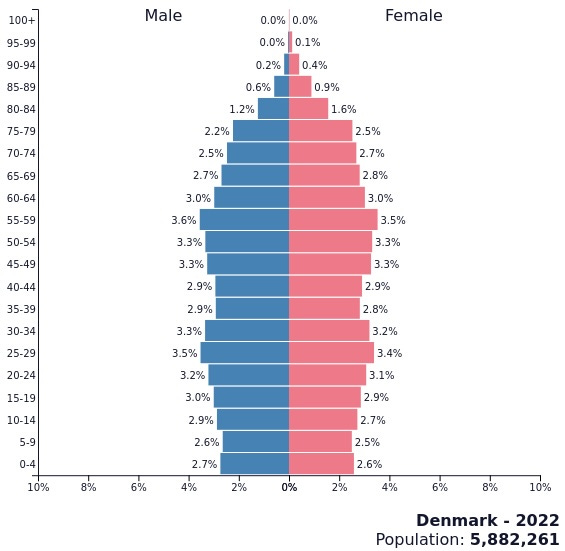

But who pays for that? Taxation that derives (principally) from the productive parts of the economy, aka younger folks. Let’s take a quick gander at Denmark’s population pyramid shall we, seeing as I have it at hand:

That’s already a lot of older Danes, or as you would say in Danish deeayeeghemaaaelghe daaaenske. Can I just say that I kind of admire the Danes for the fact that, while they are perfectly aware of the existence of consonants as evidenced by their written language, when they actually speak, they are all like, fuck it, who needs consonants, producing a kind of mystical gibberish that sounds like unending waves of diphthongs. Is there Danish rap? Is that even possible? Anyway, back to the point at hand. So, over 40% of the population is, like me, over 50. And although Denmark’s fertility rate of 1,7 is, in fact one of the higher in Europe (which, for a reason I can’t quite explain, I find surprising), it is still well below the replacement rate, which means that the winnowing of the population pyramid at the base will only continue.

Unless, of course, the government finds a way to establish a more robust support for its aging population. Which, of course, there is.

Say hello to a future, multi-ethnic – and much less Lutheran – Denmark! The country is already reliant upon immigrants in order to maintain population stability, and will become increasingly so in order to keep its accounts in balance. It turns out, you can already see the face of this future Denmark if you happen to stumble upon, as I have now just done, a playlist of Danish rap music, which, yes, does exist. Meet Gilli, KESI, and Benny Jamz, purveyors of fine Dansk Rap and representative of the multiethnic, diverse, and cosmopolitan future of the country:

Now, you might ask, what has Benny Jamz and his boys, rapping about the good life in Ibiza, got to do with Alexis de Tocqueville? Well, let’s take a quick dive into Danish politics to gauge the willingness of the country to embrace this inevitable feature of their demographic future.

That, as it turns out, is harder than you might think because Denmark has about as many political parties as it has people. But as you can tell just by the names of some of these parties, they’re pretty much all about hating on the immigrants. Among others we have the Danmarksdemokraterne (Denmark Democrats – following the rule that to signal your anti-immigrant stance you put Country Name + Democrat to show you want to keep your democracy, uh, let’s say, pristine), the Dansk Folkeparti (Danish Peoples Party), which is not to be confused with Det Konservative Folkeparti (The Conservative Danish People’s Party) and the Nye Borgerlige (New Right). While these are all currently marginal parties, having garnered together about 20% of the popular vote in the last election, they all pretty much follow the line laid out in the party platform of the Dansk Folkeparti (DF), which states (and this is a direct quote from the English version of their founding manifesto) “Denmark is not an immigrant-country and never has been. Thus we will not accept transformation to a multiethnic society.” In the elections of 2015, the DF won the second largest number of seats in the Danish parliament (Folketing), which, in a pattern that has been repeated elsewhere across Europe, pushed the country’s mainstream centre-conservative party further to the right (which is pretty ironic given that the party’s name is Venstre, or “Left”). Since their shellacking in 2015, Venstre has adopted increasingly nativist policy positions to shore up its right flank against all the “people party, God-King-and-Country” movements.

Now, I have absolutely no idea who the typical supporter is of the Dansk Folkeparti and their ilk, but if I had to make a semi-educated guess, it would be white and old. And cranky, definitely cranky. I suspect you don’t hear a lot of Gilli, KESI, and Benny Jamz at a DF rally. But of these, it is the old part that matters, because – and this is where Denmark simply offers a microcosm of the larger political landscape in many, many developed countries – as the Danish population continues to grow even older, I would not in any way be surprised if we were to see an increase in the support of what I might call a gerontological politics, chiefly characterized by dismay that Denmark is, in fact, transforming into the very multiethnic society that these parties rail against.

The degree to which the undiluted nativism of these right-wing party platforms will end up mainstreamed inside the politics of developed countries remains, of course, unclear. But the near-term trend is not encouraging. As I noted in a post about the Dutch election winner of a sort, Meneer-amazing-hair Geert Wilders, the capacity of the voting electorate to remain willfully blind to the inevitable demographic realities of the next decades should not be underestimated.

You may recall the remarkable feat pulled off by the former German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who managed to hoover up a million refugees from places like Syria and Afghanistan in 2015. That year, a wave of migrants flooded into Europe after Turkey (where the vast majority, perhaps some 4 million, of displaced Syrians sought refuge and a major transit point for others moving from East to West) suddenly opened its borders. This provoked a sudden surge of people, which not only overwhelmed the existing facilities in Europe for processing refugee applications, but also provided an alarming visual demonstration of what mass migration could look like.

Merkel saw an opportunity and announced that anyone who could make it to Germany would be given refuge and famously declared in the face of not inconsiderable discomfiture at this prospect that “wir schaffen das” (we can manage it). As a result, Germany took in 1,2 million people during this period, a gesture for which Merkel won the UN’s Nansen Prize (called by the UN its “Refugee Prize” which – is it me? – seems like an odd billing.)

The thing is that, while Merkel billed the gesture as one of “compassion,” a “humanitarian imperative” that reflected European values of open-mindedness and commitment to freedom, it is hard not to conclude there was an ulterior motive. This is because the humanitarian gesture very conveniently coincided with demographic necessity. Let me just observe that, on the one hand, we have the sudden presence of a million, mostly young people placed temptingly a train ride away from the German border, while on the other we have a German state whose demographic profile is rapidly getting older and whose fertility rate (in 2015) was under 1,5. So it seems pretty clear that the humanitarian imperative nicely aligned with what we might call a demographic imperative. And nothing wrong with that. Sometimes the right thing to do on humanitarian grounds can certainly be consistent with larger strategic interest. But the interesting thing is that this massive people grab had to be sold to the German public, not as an opportunity to maintain the viability of the country’s social system by helping to rebalance the population pyramid – that is, as something in the self-interest of the German state – but rather as a gesture of selflessness.

That episode reveals the patterns taking shape inside the political discourse of many developed economies. The main far right-wing German political party, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which in the 2013 elections couldn’t even cross the minimum threshold for representation in the German Parliament, rocketed into third place in the elections following Merkel’s refugee grab (in 2017). And in Sweden, which had also taken in a bunch of refugees during this period and for the same reason, the main political beneficiary in the next election was the anti-immigrant Sverigedemokraterna party (about which, see party naming rule above).

There is a lazy trope, perpetrated by (especially US) media, that many parts of Europe are in the grips of a right-wing, nativist, anti-immigrant, often Euro-sceptical wave of political reaction. That is, for now, an exaggeration to the point of caricature, because such positions, while certainly growing in support, still remain generally at the margins of mainstream discourse, representing (with some exceptions, like Hungary) well below the majority of the population.

But, if things are not so bad now, the trend is worrying. And this is because, while everything I have noted so far is blindingly obvious and hardly worth having wasted your time reading about, there is an additional problem that low fertility developed economies face. Which is that, even as countries like Germany or Sweden or France or Spain or Norway have to contend with the challenge of balancing existing popular attitudes to immigration and deep-rooted desires to keep their countries as they are, with an unavoidable reliance on immigration to maintain the viability of their existing social and economic structures, the problem is going to get worse.

When someone from, say, Algeria immigrates to France, or from Afghanistan to Sweden, or Syria to Germany, they – and especially their offspring – become unavoidably French, Swedish or German. Which is not to say that they necessarily become culturally assimilated – often far from it for reasons that have to do with larger social attitudes, ethnic balkanization, structural exclusion, etc…. But in purely demographic terms, that matters much less than the fact that such people, by moving to France, Sweden or Germany, are also moving into the reality of the second demographic transition. So second or third generation Algerians living in France, for instance, even were they to remain firmly within a culturally familiar community and reproduce the social attitudes of their forebears (which is itself unlikely), nonetheless their reproductive patterns conform with remarkable speed to those of the society around them. Which makes sense. Because if the logic of the SDT is linked to the larger socio-economic reality (economic anxiety, educational opportunity, female attainment, etc…) then anyone, regardless of where they were from originally, will as a matter of rational self-interest conform to that logic. Thus, with respect to their fertility patterns, those of immigrants will typically converge with the native-born. And the pace of that convergence is accelerating, meaning that immigrants and, especially, their children can be expected to produce fewer offspring now than those same would have had two generations ago.

So this means that the path of, not just European, but all economies that trigger the second demographic transition is inevitably towards a fate that is either a much emptier country, or else a transition to a state that is multicultural and multi-ethnic. For some countries, like Argentina, Canada, or New Zealand, which have a kind of cosmopolitanism baked into their national DNA, this will be easier. A quarter of all Canadians, for instance, are immigrants, a fact that the Canadian government pointed to proudly in a news release, which then continued:

Given that the population of Canada continues to age and fertility is below the population replacement level, today immigration is the main driver of population growth. If these trends continue, based on Statistics Canada's recent population projections, immigrants could represent from 29.1% to 34.0% of the population of Canada by 2041.

This is the Danmarksdemokraterne nightmare. Because Denmark faces the same problem (although with its slightly higher birthrate not quite as soon), and thus if it wishes to maintain population stability, let alone population growth to ensure the integrity of its existing social system, the only solution is to bring people in from abroad. And – to keep bringing them in.

So going forward, the optics of immigration will only intensify, and the political reaction that has been inspired so far will, I predict, only get worse. Of course, as new citizens make up a growing share of the population, ethnic nativism will be balanced out by the emerging diversity of such states. But the process, I think, is going to be messy: rhetorically ugly and politically divisive. And the core logic of the debate - a simple demographic reality that cannot be denied – will be drowned out by emotional arguments about maintaining the integrity, and (one suspects) historical ethnic character, of national identity.

The author Mavis Gallant once defined a Canadian as “someone with a logical reason to think he may be one.” As a Canadian, the deep truth of that remark resonates. But the problem is that most countries don’t have anything like the ephemeral identity of a Canada. Nor do they have the internal cultural mechanisms to allow for the inevitable redefinition of what it means to be a Dane, a Japanese, or a German to be a process that can be made readily comprehensible. The Japanese solution – to hold on to what it means to be Japanese and somehow hope for the best as the society slips into ever greater degrees of superannuation – is certainly an option. But not a very good one. Insofar as this is not a generally palatable solution, then the alternative is a transition to a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, cosmopolitanism that, because of its relentlessness, will eventually force current modes of national consciousness and cultural self-understanding to confront demographic reality.

We therefore should heed the advice of de Tocqueville almost two hundred years ago. This is the coming political reality; it is going to happen, whether we like it or not. And so the best thing, surely, is not to pretend it can be stopped by voting for different flavours of nativist democrats, but instead recognise that tomorrow’s societies will be vastly different from today’s, and that we should be crafting a new politics “for,” as de Tocqueville put it, “a world altogether new.”

Thanks for reading and, as always, please share this post with anyone who might be interested and if you made it this far, please give it a like.

If you had replaced "political" with "Technology", and "right-wing" with "Regulations" , this article would still be true for Europe..

Its possibly just a European thing to hold onto the old, trying to fight the inevitable